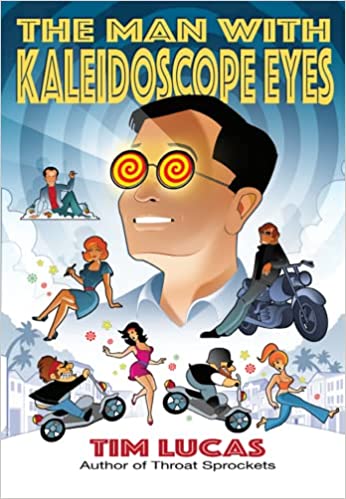

By TIM LUCAS (PS Publishing; 2022)

By TIM LUCAS (PS Publishing; 2022)

The current fascination with fictionalized depictions of late 1960s Hollywood, as depicted in Zachary Lazar’s novel SWAY and Quentin Tarantino’s ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD (film and novelization), continues apace with THE MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES, a novel by Video Watchdog’s Tim Lucas. The subject is one near and dear to the hearts of Lucas and film buffs the world over: Roger Corman and his 1967 drugsploitation classic THE TRIP. Offered up is a fictionalized depiction of Corman, as well as the film’s principals Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Bruce Dern, its screenwriter Jack Nicholson and hangers-on like Peter Bogdonovich and Corman’s longtime assistant Frances Doel. The book’s galvanizing event is the actual LSD trip Corman claims he took to prepare for the shooting.

The book’s galvanizing event is the actual LSD trip Corman claims he took to prepare for the shooting.

THE MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES began life as a 2004 screenplay by Lucas and Charlie Largent (with subsequent contributions by Michael Almereyda and James Robison). Joe Dante has tried for years to bring that script to the screen, but without success. This novel, Lucas claims, was conceived as a “creative way” to attract attention to the project.

Not having read the script, I can’t say how it differs from the novel. What I can say is that the latter is a mighty enjoyable read, with a portrayal of Roger Corman that feels accurate (the man himself has reportedly given his full blessing to the project) and a scrupulously researched portrait of Hollywood in the late 1960s.

… a mighty enjoyable read, with a portrayal of Roger Corman that feels accurate…

It’s then that Corman, having scored an unexpected hit with the bikersploitation classic THE WILD ANGELS, decides to tackle the then-topical subject of LSD. A scrupulous, buttoned-down type with who eats the same breakfast every morning and constantly has three film projects moving forward at once (“one in the editing room, one ready to shoot, and another in the typewriter”), Corman gets his writer pal Chuck Griffith to script THE TRIP. This results in an unwieldy concoction that’s given a top-to-bottom rewrite by Nicholson, then known as a B-movie actor who worked almost exclusively for Corman. Shooting commenced around the time LSD possession was criminalized in California, which Corman, always on the lookout for an exploitable promotional angle, viewed as a positive development.

Of the LSD trip that gives this book (like THE TRIP) its raison d’etre, it takes place in Big Sur, and has Corman interacting with his parents and ancestors, humping the earth and travelling to the planet’s center, where he “discovers” the concept of underground movies. The language in this portion grows quite fluid and discordant (“something once washed up ashore to be hastily chronicled in dense rock that it might be recorded before decomposing under time’s boot into myth and memory”), although the prose calms back down for the final chapters. In them Corman finds himself becoming a more grounded and less rigid individual as a result of his trip, breaking off his lucrative but artistically unrewarding association with American International Pictures, getting together with his future wife Julie and, with THE TRIP, creating what Lucas correctly identifies as one of Corman’s most personal and all-around satisfying motion pictures.

Yes, this book is a rarity in the annals of modern drug literature in that its depiction of LSD is an unabashedly positive one. It’s for this reason (it’s been opined) that the MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES screenplay has been unable to interest financiers; as Dante reportedly stated, “If Roger had taken acid and became a hatchet murderer, we’d have no problem!”

…as is the inevitable case with most anything written by Lucas, the book is profoundly nerdy.

One more thing: as is the inevitable case with most anything written by Lucas, the book is profoundly nerdy. This is an author who once likened viewing a restored print of Mario Bava’s BLOOD AND BLACK LACE to “being touched by the hand of God,” and that spirit is evident in a dissertation on Corman’s major psychological dilemma—prefaced with the observation that “one of the most significant dichotomies in the human animal is the favoring of logic over emotion, and vice versa”—and the many unsubtle shout-outs to past and future films by THE TRIP’s principals, as in a passage in which Nicholson finds himself scrawling the words “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” while writing his script, and Corman shouting “I can still see!” during his acid trip. Such overt nerdishness didn’t stifle my enjoyment of the book, but it was a periodic distraction, akin to speed bumps in an otherwise lovely ride.