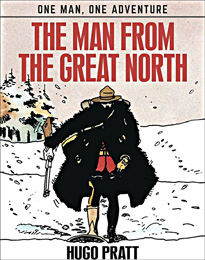

By HUGO PRATT (IDW; 2017)

Another interesting release from IDW Publishing that was done in by poor distribution. Previous examples of mishandled IDW publications include SHOCK FESTIVAL and BILLY MAJESTIC’S HUMPTY DUMPTY, neither of which ever got a fair a shake in the marketplace, and vanished from print very quickly. A similar fate seems to have befallen THE MAN FROM THE GREAT NORTH, a beautifully designed English rendering of a 1980-82 graphic novel by Euro comics legend Hugo Pratt that’s considered a classic in its original Italian language form.

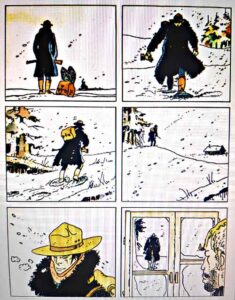

This publication, translated by Dean Mullaney, Simone Castaldi and Ariane Levesque Looker, comes complete with storyboards Pratt drew for a 1991 film adaptation and rough sketches discovered among Pratt’s personal files. This makes for visuals that are highly uneven, with detail-free scribbles clashing with the artful and atmospheric illustrations of the original publication, but at least this highly enigmatic tale has been rendered more coherent than it initially was.

It’s the story of Jesuit Joe, an odd and mysterious character inspired by Louis Riel, who in the late 1800s led multiple Métis (mixed race indigenous Canadian) uprisings against the Canadian government. Jesuit Joe has been described by his creator as “the crazy Métis who, in fact, was not at all crazy but simply different.” The introduction by Gianni Brunoro, meanwhile, characterizes J.J. as a man on “an endless search for the Absolute.” Myself, I feel that as depicted here this guy, hailing from “a family of mad visionaries,” does indeed seem quite crazy, with the “absolute” he’s supposedly seeking never seeming too clear.

It opens in autumn, with Joe nonchalantly entering the Canadian wilderness-based house of a Mountie and stealing his red jacket. There follows a shootout with two men, with Joe demonstrating a disturbingly nonchalant attitude toward killing. He also likes scalping his victims and shooting birds out of the sky, lamenting there’s “Too much happiness in these woods.”

He next happens upon a kidnapped infant and kills its First Nations captor. As fall turns to snowy winter several more killings are in store, with victims that include Joe’s prostitute sister and a bear. Yet the man is also capable of empathy and compassion toward the downtrodden, suggesting he has a (twisted) moral code. Pursuing him is the law enforcement officer whose jacket Joe stole, in route to a highly ambiguous conclusion.

Contained in this publication are 19 pages of an incomplete sequel to the above. Those 19 pages resolve the mystery of what occurred at the conclusion of the previous story, but “end” on an even more unresolved note.