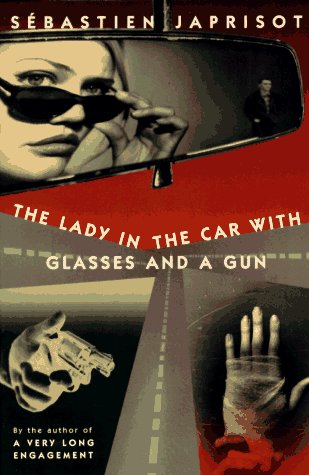

By SEBASTIAN JAPRISOT (Penguin; 1967)

By SEBASTIAN JAPRISOT (Penguin; 1967)

A most intriguing exercise in psychological displacement in the guise of a crime thriller, this twice-filmed novel by France’s Sebastian Japrisot (actually Jean-Baptiste Rossi) is a confounding masterwork. It’s extremely European in temperament but has much in common with the novels of America’s John Franklin Bardin, being a crisply written potboiler with a teasingly hallucinatory edge.

It begins with an alluring young blonde, who identifies herself as Dani and has extremely bad eyesight, coming to in a public restroom. She’s just been attacked by an unknown someone, with her major crime, she claims, being a desire to “see the sea.” We learn she was hired the day before by her boss Michel, an advertising tycoon for whom Dani works as a secretary, to type up some documents at his house, and the following morning drive him and his wife to the airport in his snazzy Ford Thunderbird. All this Dani does, but instead of driving the car back to Michel’s house as promised Dani impulsively takes off on an aimless sea bound jaunt. This is despite the protestations of her deceased mother, whose imagined figure is always at Dani’s side.

Clearly this young woman isn’t entirely well, and her mental state only grows more strained following the seemingly random attack that opens the novel. Even more disconcerting, the many strangers with whom Dani comes into contact on the road all claim to recognize her, the Thunderbird she’s driving and, most confounding of all, the hand wound she received in the restroom attack.

Following several more odd events Dani opens the trunk of the Thunderbird, and finds a dead body within. This precipitates a near complete psychotic break, with Dani coming to question her recollection of recent events, her identity and the very nature of reality, which only appears to be growing more slippery and insubstantial by the minute. Not to worry, though, because there is a rational (if implausible) explanation that’s revealed in the final chapters, marked by a jarring (though necessary) viewpoint shift. Yet what ultimately lingers is the atmosphere is hallucinatory disquiet that pervades much of the rest of the book, which is as vivid and unnerving as anything ever imagined by Stephen King.