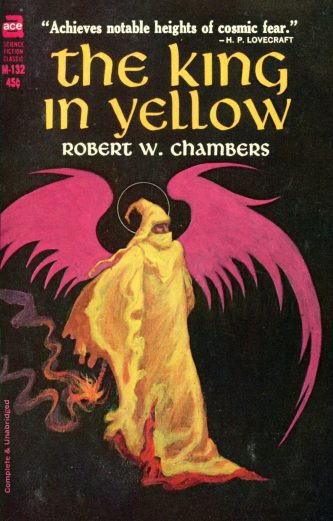

By ROBERT W. CHAMBERS (Ace; 1895)

By ROBERT W. CHAMBERS (Ace; 1895)

After reading this Nineteenth Century classic I couldn’t help but flash back to Stephen King’s words about FRANKENSTEIN the novel: “Readers expect a souped-up Edgar Allen Poe tale or perhaps a 19th Century Stephen King novel. And they are, for the most part, disappointed.”

This is to say that I was indeed expecting far more from the collection THE KING IN YELLOW than what it contains—although I wasn’t entirely disappointed. Parts of it convey a type of hallucinatory dread that fully justify the considerable praise afforded the book by H.P. Lovecraft, who admittedly constructed his Cthulhu Mythos around it.

But what neither Lovecraft or the publishers of the numerous editions of this book reveal is that of THE KING IN YELLOW’S ten stories, only a few can fairly be classified as horrific. I’m referring to the first four pieces (“The Repairer of Reputations,” “The Mask,” “In the Court of the Dragon” and “The Yellow Sign”), each linked by an accursed text that provides the title.

The first tale is set in the “future” year 1925, with a man driven mad by reading a long-censored play that gives this book its title, which causes him to become obsessively fixated on “Carcosa where black stars hang in the heavens; where the shadows of men’s thoughts lengthen in the afternoon, when the twin suns sink into the Lake of Hali.” That passage is one of several tantalizing hints of what lurks within this accursed text, calling to mind snatches of a partially remembered dream.

“The Mask” involves a solution that can turn flesh into marble, with its protagonist again reading from THE KING IN YELLOW. This affords us another vivid glimpse of its contents: “I saw the lake of Hali, thin and blank, without a ripple or wind to stir it, and I saw the towers of Carcosa behind the moon.” “In the Court of the Dragon” features a church-goer, having read from the forbidden book, pursued by a forbidding figure. The tale ends on a grim note: “I sank into the depths, and I heard the King in Yellow whispering to my soul: “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God!”

The finest, most disquieting tale is “The Yellow Sign.” It concerns a painter who finds himself coloring an attractive model’s skin a sickly tone after spotting an ugly church watchman. The painter later encounters the watchmen, who repeatedly mutters “Have you found the Yellow Sign?” The painter discovers what is meant by this upon reading the titular play together with an attractive model/love interest, who has given him a weird talisman engraved with the sign in question. The two spend hours murmuring about “the king and the Pallid Mask…of Hastur and Cassilda” while “outside the fog rolled against the blank window-panes as the cloud waves roll and break on the shores of Hali.” But then the church watchman makes a final appearance, all locks melting at his touch, as “no bolts, no locks, could keep that creature out who was coming for the Yellow Sign.”

Unfortunately that’s the last we hear of the tantalizing and mysterious KING IN YELLOW. Of the remaining stories, “The Demoiselle of D’ys” has a man falling in love with the specter of a long-dead woman. “The Prophet’s Paradise” is a prose poem about a poet’s search for true love. “The Street of the Four Winds” is about a cat, a grieving widow and the corpse of his beloved. “The Street of the First Shell” is a war story set in Paris of 1870. “The Street of Our Lady of the Fields” and “Rue Barree” both concern Americans finding romance in bohemian France.

The latter stories aren’t entirely unworthy (the poetic “Street of the Four Winds” is rather effective), but they pale in light of the overpowering disquietude of the first four, and that unforgettable book within the book. The KING IN YELLOW play remains a singular and haunting creation, but this book suffers from off-putting Victorian sentimentality and wildly uneven contents. At its best—which is to say “The Yellow Sign”—it’s a triumph of awe-inspiring cosmic dread, and if the other tales were up to the same standard this book would indeed be a genre masterpiece. But they aren’t and it’s not.