By COLIN WILSON (Savoy; 1970/2002)

By COLIN WILSON (Savoy; 1970/2002)

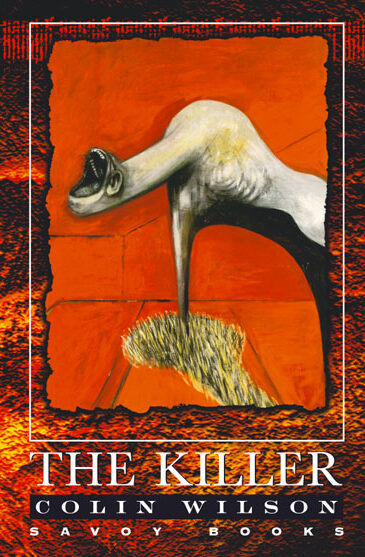

The apotheosis of the British author/philosopher Colin Wilson’s crime fiction was THE KILLER, presented by the UK’s Savoy Books in its most complete version (with all others, including an American edition titled LINGARD, censored to varying degrees). Extras unique to the Savoy edition include striking jacket design by John Coulthart and a lengthy introduction and afterward by Wilson, who details the novel’s conception and publication history.

As with Wilson’s previous crime novels RITUAL IN THE DARK (1960) and THE GLASS CAGE (1966), THE KILLER was based in part on an actual criminal: Peter Kürten, the 1920s-era “Vampire of Düsseldorf,” mixed with other widely publicized 20th Century crimes. As with THE GLASS CAGE, the novels of Thomas Harris are foreshadowed in THE KILLER’s frank and unsensational approach to sexual deviation and mass murder, as are A.E. Van Vogt’s THE VIOLENT MAN (1962) and accompanying pamphlet A REPORT ON THE VIOLENT MALE, which Wilson discusses at great length in his afterward, proclaiming it “one of most important and revolutionary statements I have ever read.”

In a departure from Wilson’s other crime novels, which suffered from cluttered narratives and haphazard attempts at mystery novel construction (a format in which Wilson had little-to-no interest), THE KILLER maintains its focus. Written in a four week “fever of inventiveness,” it relates the life of Arthur James Lingard, an incarcerated rapist and murderer. The narrator is Dr. Samuel Kahn, a prison psychiatrist who becomes intrigued by Lingard, feeling he’s far more dangerous than the “more or less harmless and trustworthy” patient the prison authorities believe he is.

After interviewing the consistently unpredictable Lingard and becoming privy to his elaborate and horrific fantasies, Kahn meets with Lingard’s foster parents and sister Pauline. From these interviews he draws up a lengthy biography of Lingard, marked by an impoverished working-class childhood and an overtly incestuous affection for the sexually uninhibited Pauline. As Lingard aged his repressed desires manifested themselves in acts of petty thievery and panty hoarding, leading to house break-ins to steal ladies’ undergarments and, utilizing a talent for hypnotism, sexual coercion. This in turn led to the murders that landed Lingard in prison.

Kahn, however, believes there’s more to the story, and deduces that his initial suspicions about Lingard’s true nature were correct. As revealed in the final thirty pages, the man is indeed far more dangerous than he lets on, having committed numerous rapes and murders in addition to the crimes described above.

Wilson takes a frank, documentary-like approach to his subject matter. That tendency extends to the descriptions of sex and violence, which aren’t sugar-coated in any way (and apparently resulted in more than one publisher rejecting the manuscript outright), yet Wilson’s sure grasp of abnormal psychology is undeniable, and was presented in here in its most concentrated and unflinching form.

One issue I have is with the character of Dr. Kahn. A just-the-facts-ma’am investigator, Kahn has none of the nuance and complexity that animate Lingard. The idea that Kahn might be psychologically impacted for better or worse by his immersion in Lingard’s psyche is never breached (even though it would seem like a worthwhile avenue of exploration), thus allowing the aforementioned Thomas Harris to take that idea (intentionally or not) and run with it a decade later.