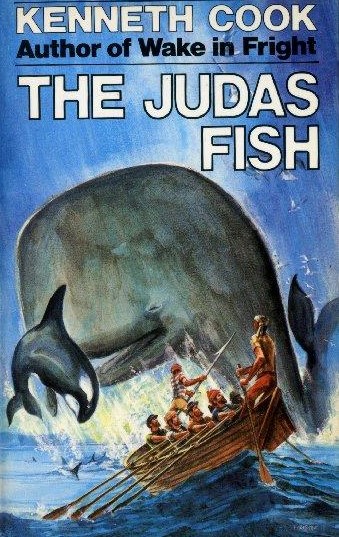

By KENNETH COOK (Rigby Publishers; 1983)

By KENNETH COOK (Rigby Publishers; 1983)

The late Kenneth Cook was never more inspired than he was in this novel, a paperback original that appears to have come and gone without much notice. The subject is the Australian whaling industry of the 1840s, a long-vanished world Cook brings to life with great vividness, and content that, as the author concedes in a brief nonfiction forward, often seems downright outrageous. Included is a two page bibliography of books used as research, to “justify the bizarre quality of many of the events which as a novelist I simply would not dare invent.”

In THE JUDAS FISH Jonathan Church, a naïve young man, finds work as part of a whaling crew in Three Folds Bay, a coastal village in New South Wales ruled over by David Hoyle, an amoral, power-mad shithead (the character was inspired by the 19th Century Australian entrepreneur Benjamin Boyd, and the comparison, you can be sure, is not at all flattering). Hoyle makes his fortune primarily through whaling, which as described here involves dozens of men packed into tiny boats who are led to their prey by the titular Judas and his fellow “fish”—killer whales, actually, who feel no loyalty to the much bigger right whales the men hunt.

Those hunts are wrenchingly bloody affairs, involving grueling and protracted bouts of stabbing at the massive whales until they die, with the local shark populations unwittingly aiding the men in their nasty business. Those men, I should add, don’t always fare much better than their prey, frequently emerging from the hunts crippled, crushed and even decapitated.

Things heat up when Jonathan falls for Yoko, a Japanese immigrant, and becomes involved in a questionable scheme cooked up by Hoyle. The latter suffers from lumbago, which can apparently be alleviated by immersion in the guts of a whale. This Hoyle initially attempts, with Jonathan’s help, in a days-old whale carcass (doubtless one of the “bizarre events” referred to above), which does little for his condition.

Hoyle decides to make a second attempt utilizing the innards of a freshly slaughtered killer whale, again with Jonathan’s help. This puts Jonathan in a most uncomfortable spot, as the killer whales, whose ranks include the all-important Judas, are integral to the efforts of Jonathan and his fellow whalers. Hoyle sweetens the deal by providing Jonathan with a swank cottage in place of the shack he initially calls home, which goes a long way toward putting Jonathan’s apprehensions to rest. That, however, doesn’t change the fact that the deal is a bad one, with unpleasant consequences for everyone involved.

The narrative focus is diluted somewhat in the book’s latter half, in which Jonathan is drawn into a dive for an impossibly valuable pearl in a sunken ship—a gambit organized by Tom Cassidy, an American businessman afoot in Australia for questionable purposes. It’s an odd detour that diverts a gritty fact-account into TREASURE ISLAND territory, although it leads to a satisfying sea-set climax that neatly ties together the book’s characters and motifs.

Bluntness was one of Cook’s standout qualities as a storyteller, and definitely makes itself evident here. A deceased whaler is remembered as “A man who was prepared to risk his life for an absurdly low sum of money,” while the specter of slavery and the attendant racism are faced up to quite directly. On the subject of inter-racial coupling we’re informed that “blacks were there to be used when convenient,” and Jonathan is harassed at one point for being a “chink lover.”

Such an unflattering portrayal of Australia’s heritage might be what sunk this book commercially. In this respect THE JUDAS FISH stands alongside Cook classics like WAKE IN FRIGHT and BLOODHOUSE, whose primary virtues are their unwavering commitment to the harsh realities of life in their author’s native land, in which respect those books, and this one, were and remain without parallel.