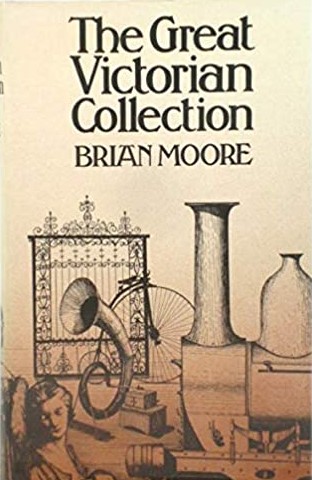

By BRIAN MOORE (Ballantine; 1975)

By BRIAN MOORE (Ballantine; 1975)

The late Brian Moore wrote numerous novels of varying subject matter, all distinguished by crisp, robust prose and page turning readability. Only one of those novels, 1983’s so-so COLD HEAVEN, can truly be classified as horror. Yet for thought provoking dark-hued fantasy I much prefer Moore’s GREAT VICTORIAN COLLECTION, the surreal flipside of COLD HEAVEN.

Both novels are set in Northern California’s scenic Carmel, and contain supernatural-tinged narratives that in both cases were evidently made up as they were written (Moore admittedly didn’t always bother coming up with a beginning, middle and end when he sat down to write his novels). The major difference between the two is that while COLD HEAVEN largely fizzles out after its riveting opening (also a problem with the Nicolas Roeg film adaptation), THE GREAT VICTORIAN COLLECTION compels one’s interest throughout, despite an admittedly meandering narrative.

THE GREAT VICTORIAN COLLECTION is a dark Kafkaesque reverie that works primarily because it treats its blindingly surreal concept in a staunchly realistic manner. In this respect the uneventfulness of the narrative actually works in the novel’s favor, forcibly delineating the problems one would doubtless encounter in dealing with the fantastic in modern America.

The central character is Anthony Maloney, a Toronto-based College professor with a passion for all things Victorian. One night while staying in a Carmel hotel Maloney dreams of a vast collection of Victorian artifacts—toys, furniture, statues and even some vintage pornography—situated in the closed-off parking lot outside his room. When he wakes up the following morning Maloney finds to his stupefaction that he’s literally dreamed the Great Victorian Collection into existence. The remainder of the novel details Maloney’s attempts at adjusting to this bizarre occurrence.

From the start there are problems. The hotel manager isn’t at all pleased about the sudden appearance of Victorian artifacts in his parking lot, and before long Maloney is besieged by authorities of every stripe inquiring about the collection’s authenticity. Regarding that aspect, it seems the dreamed artifacts of the Great Victorian Collection are indistinguishable from the real things—unless Maloney tries to move them from the parking lot, in which case they turn into cheap plastic replicas.

Further headaches arrive in the form of a shady reporter eager to exploit the collection’s commercial potential and the latter’s fetching young girlfriend. They become Malone’s uneasy confidants in what turns into a veritable battle with the collection; it quickly becomes a soul-crushing burden, and Maloney eventually tries to escape it. The collection exerts an unbreakable hold on his consciousness, however (a potent illustration of the truism that your possessions will always end up owning you), and draws him back for the stark and inevitable conclusion.