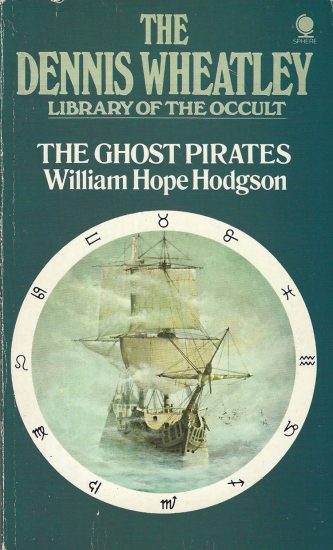

By WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON (Sphere; 1909/75)

By WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON (Sphere; 1909/75)

This was the third novel by the incomparable William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918), and one of his finest efforts. THE GHOST PIRATES contains all of Hodgson’s attributes—a compelling ocean-set narrative, a presentation of supernatural phenomena that was many years (if not decades) ahead of its time, and a most unique descriptive power—in its short and concentrated account of the Mortezestus, a ship besieged by spectral “pirates.”

What’s most striking about THE GHOST PIRATES is its impressively sustained sense of otherworldly terror. Unlike most horror novels then and now, Hodgson dispenses with scene setting and slow-building atmosphere: we learn in the opening chapter that the Mortezestus, where nearly the entire novel takes place, is haunted, and the remainder of the narrative consists of a succession of uncanny encounters with the so-called ghost pirates.

These entities are largely indistinct, but what little description we get, of a “wet glistening something, with two vile eyes,” is effective. No information is given regarding the creatures’ actions or origins, although the narrator, the resourceful seafarer Jessop, offers some unconfirmed theories involving inter-dimensional travel and the idea that the Mortezestus might be some kind of nexus for otherworldly forces. Part of Hodgson’s genius was his talent for crafting exciting narratives with a minimum of explanation, with THE GHOST PIRATES, like all of Hodgson’s best work, functioning on a dream level that nearly approaches surrealism.

Another noteworthy feature of this novel is its staunch nautical thrust. Many of Hodgson’s most famous works were nautically-themed (including the novel THE BOATS OF THE “GLEN CARRIG” and the story “The Voice in the Night”), with THE GHOST PIRATES being perhaps the foremost example. Framed as it is as a recollection by Jessop to his ship-bound rescuers, the many nautical terms he offhandedly employs, such as “fo’cas’le” and “mizzenmast,” are used authoritatively (as Dennis Wheatley, an experienced seaman in addition to a famous writer, confirms in his introduction). The same is true of the salty dialect of the sailor protagonists (example: “It’s as diff’rent as chalk ‘n’ cheese ter what it were w’en we started this trip. I thought it were all ‘ellish rot about ‘er bein’ ‘aunted; but it’s not, seem’ly”). Far from slowing things down, Hodgson’s nautical knowledge lends the story a real-life grounding of a type it takes lesser writers half a novel to build up, which of course only serves to enhance the horror.