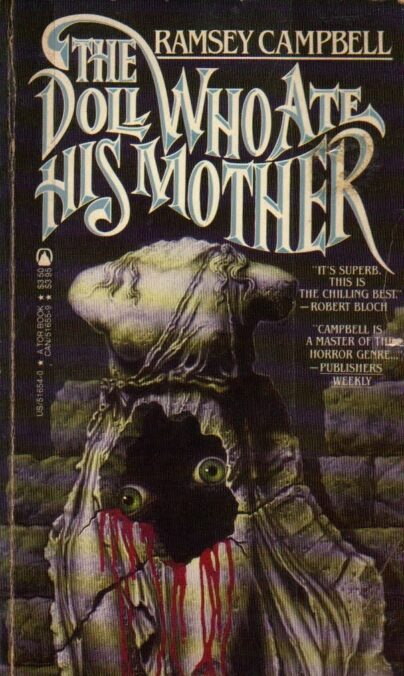

By RAMSEY CAMPBELL (Tor; 1976/85)

By RAMSEY CAMPBELL (Tor; 1976/85)

The first novel by Ramsey Campbell, and a mixed bag. THE DOLL WHO ATE HIS MOTHER lacks the focus and confidence of Campbell’s later books, offering an unwieldy combination of gritty realism, crime procedural and the type of B-movie horror the title portends. Later editions feature a 1992 afterward in which Campbell essentially apologizes for the novel’s shortcomings, admitting that “The first draft took only five months, and I believe it shows.” There’s a reason, however, that Stephen King devoted a portion of his nonfiction overview DANSE MACABRE to the novel, which stands as a readable and altogether unique concoction.

It begins with Clare Frayn, a schoolteacher with (as is constantly reiterated) stubby legs, involved in a car crash. The cause of the accident, which takes the life of her pothead brother Rob, is an unseen someone who flees the scene with one of Rob’s arms.

This nefarious individual doesn’t remain unidentified for very long. The man, it quickly transpires, is named Christopher Kelly. He’s identified by Edmund Hall, a true crime writer and childhood colleague of Christopher who’s seeking to write a book about his deranged (Edmund maintains) former schoolmate. He and Claire team up to track down Kelly, and are joined by George Pugh, a cinema owner whose mother was killed by the man, and Chris Barrow, an apparently gay fellow whose cat fell victim to Kelly’s evil proclivities—and who provides the requisite love interest.

Not all is as it seems, as the investigation uncovers black magic, malevolent doll making and a half-mad old woman who serves as a stand-in for the author’s mother (as described in Campbell’s autobiographical preface to THE FACE THAT MUST DIE). It all leads to a climactic revelation contained in a basement (a la PSYCHO), and a suitably brooding coda that foreshadows what was to come from an author who largely disdained happy endings.

Another foretaste of things to come is evidenced in the novel’s depiction of Campbell’s native Liverpool. If anything the city is overdetailed (as one internet commentator noted, “Campbell certainly likes his descriptions of things”) in an excess of gritty minutia that overwhelms the hallucinatory prose for which the author is known (although there are certainly hints of the latter in descriptions like “the shadows of the columns crept out from behind their stones and across the front doors, spreading”).

In terms of characterization the novel excels. Each of its protagonists emerge as distinct and interesting (albeit never particularly likeable) individuals. That’s especially true of the stubby-legged Claire, whose cynical exterior conceals a touching guilelessness, as is evident in the final pages, in which she misinterprets a fumble by the antagonist as an act of love—and the fact that the reader knows better doesn’t make her naivety any less touching.