By JERRY LEWIS, JOAN O’BRIEN, CHARLES DENTON (1972)

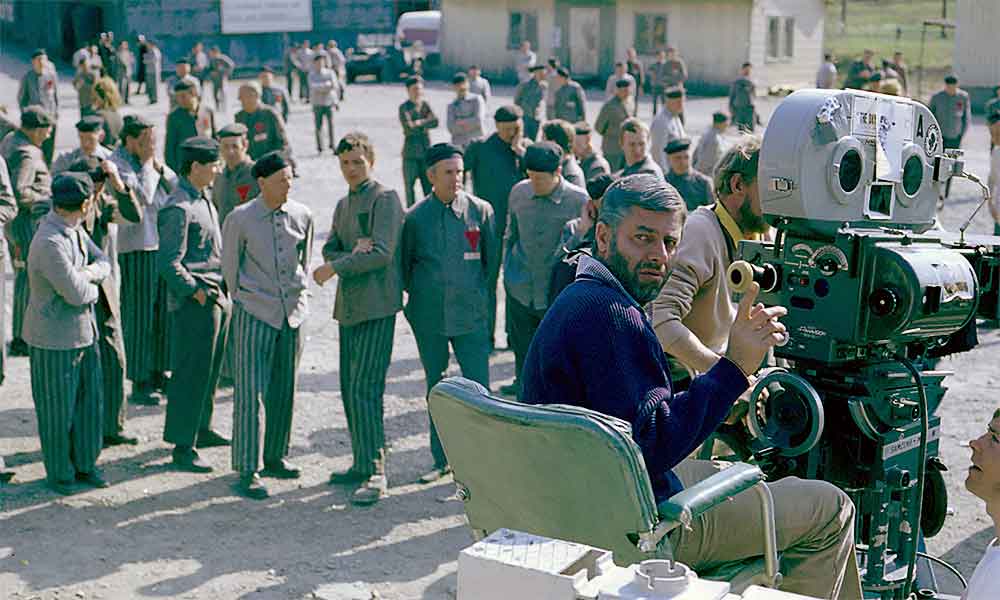

The most notorious “lost” film of our—if not all—time is THE DAY THE CLOWN CRIED. Directed by and starring Jerry Lewis, who lensed this “Family Film” in Paris and Stockholm in 1972, it was (depending on who you ask) either never completed or completed and never released. The film has, needless to add, taken on legendary status in the ensuing decades, seeming to validate the comments of Harry Shearer (who claims to have clandestinely viewed it), who stated that “seeing this film is really awe-inspiring…so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is.”

Reading Lewis’ shooting script, a rewrite of an original screenplay by Joan O’Brien and Charles Denton (from whom Lewis apparently didn’t bother obtaining the rights), two things are immediately clear: 1). The film is indeed pretty bad, and 2). It’s not quite the train wreck the Shearer comments portend (I base that opinion on the thirty minutes of footage that dropped onto the internet in 2015 in addition to the screenplay).

It’s the story of Helmut Doork (which, as the script makes sure to specify, is “pronounced DOOR-K”), a “depressed and very unhappy clown” in 1940s Germany. Self-pity is this guy’s major (and, it seems, only) character trait, which gets him into a heap of trouble when during a drunken whine-fest he insults Hitler in front of some high-ranking Nazis. For this Helmut is sent to a prison camp where he promptly alienates his fellow inmates by refusing to entertain them.

But then some Jewish children are interred in an adjoining camp, and Helmut inadvertently catches their attention. This reawakens his love for clowning, and before long he finds himself enthusiastically performing for the kids, much to the consternation of his fascist overseers, who spend a (most unrealistic) lot of time hand-wringing over the fact that Helmut won’t comply with their wishes. Yet when the kids become stuck in a stranded box car the Nazis find a use for Helmut, ordering him to keep the kids quiet so they won’t disturb the people living in the area. He complies, accompanying the children to Auschwitz, where “they want us to move to another building…where there’ll be more room…to play and…do lots of things…,” and ultimately joins them in a gas chamber—because, when one of the kids asks if has any children, his reply is “I do now.”

The story would seem to be inspired by Janusz Korczak, a Polish educator who in 1942 accompanied an orphanage-full of Jewish children to the Treblinka death camp (an account properly dramatized by Andrzej Wajda in 1990). That, however, is about the only bearing this script has in reality, and nor does it contain much in the way of character development (with Helmut being a one-dimensional sad sack throughout) or plausibility. Still, it’s not as cosmically horrible, or offensive, as it’s been cracked up to be.

THE DAY THE CLOW CRIED is certainly no more inappropriate than LIFE IS BEAUTIFUL/La vita è bella (1997) or ADAM RESURRECTED (2008), which spun far more outrageous Holocaust-themed narratives. The difference is that the former film took the form of a screwball comedy and the latter an overtly surreal drama, whereas Lewis relates his narrative in a drearily straightforward, dour manner (an orientation bolstered by all the “Dissolve To” screen directions). This only calls attention to the many contrivances and historical inaccuracies, which portend a misguided and ill-conceived but far from horrendous film. It is, in short, a huge disappointment.