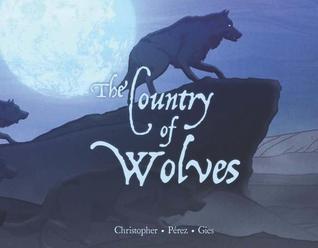

By NEIL CHRISTOPHER, RAMON PEREZ, DANIEL GIES (Inhabit Media; 2012)

By NEIL CHRISTOPHER, RAMON PEREZ, DANIEL GIES (Inhabit Media; 2012)

This gorgeously designed graphic novel fleshes out an ancient Inuit folktale. Like quite a few folktales, this one involves a lone man facing down a band of inhuman monsters, and so makes for an affecting horror story with a not-especially-happy ending.

THE COUNTRY OF WOLVES is in fact an adaptation of the animated short film AMAQQUT NUNAAR, written and directed by Neil Christopher and animated by Ramon Perez. The book, which contains a DVD of AMAQQUT NUNAAR and an afterward that elucidates the story’s spiritual overtones, consists, essentially, of stills from the film, which transfer quite well to graphic novel format.

In both film and book simplicity is key, with the particulars of the folktale presented without clutter or artifice. That sense of elegant simplicity extends to the artwork, which is precise and unadorned, and unafraid to leave large portions of a page in darkness. The purplish color scheme is arresting, and quite appropriate to a tale that takes place during a winter night in the arctic.

It involves two Inuit brothers on a nighttime hunt who become stuck on a piece of sea ice that breaks free from its moorings and floats away. It deposits the brothers in an unfamiliar land where they happen upon a mysterious village. This village is not a nice place, as one of the brothers quickly learns when he enters an igloo filled with cavorting people who turn out to be Amaqqut Inuruuqqajut, or wolves in human form.

The other brother has better luck, running into an old woman who despite being a werewolf herself deigns to help her visitor, offering sound advice on how to defeat the monsters and giving him a saggutt, a stick that when planted in the ground leans in the direction of its user’s home. What the man doesn’t realize is that he’s stuck in a ghostly region whose uncanny properties affect everything within it, including himself.

It all adds up to a wonderfully eerie account that succeeds in presenting the beliefs of a culture light years removed from our own in an accessible manner. There is, however, one element of this book—and also the above-mentioned source film—that bothered me: the intrusive narrative voice that, in an apparent attempt to reflect the story’s folktale roots, insists upon constantly explaining the visuals (example: an illustration of the brothers happening upon a village that’s accompanied by a dialogue balloon reading “A village!,” meaning there’s no need for the line informing us “They had found a village”). Yes, the text contains some memorable turns of phrase (“As they rushed over the snow, these beings released their human shape as one might take off a jacket”), but in a graphic novel format it’s best to let the illustrations speak for themselves.