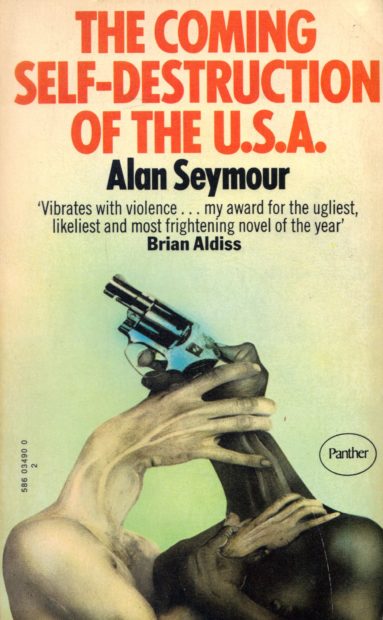

By ALAN SEYMOUR (Panther; 1969)

By ALAN SEYMOUR (Panther; 1969)

Of the many black uprising fantasies that appeared in the late 1960s and early 70s (SIEGE, MEETING THE BEAR, etc.) this is the most expansive and outrageous of the lot. Its author Alan Seymour (1927–2015) was an Australian playwright and television scripter, and his non-American status is evident throughout this ambitious account of just what the title promises.

Inspired, evidently, by the many racially-motivated uprisings of the late 1960s, THE COMING SELF-DESTRUCTION OF THE U.S.A. is an epistolary novel that consists of letters and diary entries written by participants and spectators in a twenty year black uprising that reduces America to a state of total anarchy. The characters include a black college professor who finds himself becoming increasingly attracted to both the radical politics and the violence espoused by the leaders of the uprising, a British immigrant whose outsider status makes him a popular media personality, and the unnamed editor who culls all this together as his world collapses around him.

It all begins with a racially motivated mass shooting by a white ex-Marine. From there a militant African American terrorist organization is formed by a shadowy individual known only as Hero. Although never seen, Hero proves an extremely effective agitator, inciting violent acts that inflame the white populace, who in many cities end up becoming subservient as the black revolutionaries completely take over. Hero himself is inevitably killed in the melee, and replaced by a far more ruthless revolutionary leader.

Alan Seymour deserves credit for maintaining his focus in a highly panoramic, multi-character account. What’s missing, alas, is a sense of intimacy, with the diarists tasked with telling this story failing to register as individuals and, despite the author’s best efforts, all sounding the same. That Seymour wasn’t American is evident in his oft-naïve and simplistic depiction of racial tensions in the USA (in which Hispanics are given a passing mention but Asians and Native Americans apparently don’t exist), and there’s more than a hint of racism in the hysterical actions of both the black and white characters (who invariably react to any provocation with extreme violence).

Yet Seymour gets many things right. The “white flight,” referring to white people fleeing America’s cities, that occurred in the 1960s and 70s is very much taken into account, as is the intercession of the far right into mainstream politics and the rise in mass shootings. Let’s hope this novel’s central conception, of America’s total self-destruction, doesn’t also come true, although given current events it appears increasingly likely that we’d all be well advised to hunker down.