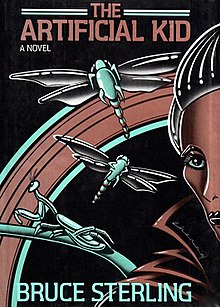

By BRUCE STERLING (Harper & Row; 1980)

By BRUCE STERLING (Harper & Row; 1980)

The book that, together with the John Shirley potboilers TRANSMANIACON (1979) and CITY COME A-WALKIN’ (1980), served as the true prototype for what by the end of the 1980s was known as cyberpunk. The second novel by Bruce Sterling, THE ARTIFICIAL KID followed INVOLUTION OCEAN (1977), which was published as part of Harlan Ellison’s Discovery Series. Ellison, FYI, called Sterling the “grand poobah of cyberpunk,” which isn’t entirely accurate (William Gibson will always hold that title), but THE ARTIFICIAL KID’S links to the movement are undeniable (and bolstered by the fact that Gibson provided an admiring introduction to a later edition). It is not, however, Sterling’s best work.

The setting is the planet Reverie, a melting pot of alien species created by the “dead” mining magnate Moses Moses. Reverie’s geography includes the Decriminalized Zone, an area in which laws don’t apply, and Telset, an island inhabited by a riot of competing biologies. Residing in this fecund environ is The Artificial Kid, a combat artist who makes blood-drenched combat videos involving martial arts and nun chucks to satisfy the ultrarich public’s taste for ultraviolence. He, like most everyone else on Telset, has multiple drone cameras constantly hovering around him, recording video footage to be edited together at a later date and posted on a something very like what we know as the internet.

Sterling’s conception of a society of slavering narcissists recording their every movement is a potent and, needless to say, prescient one. So too the idea of artificially prolonged lifespans (everyone in this universe, it seems, is well over a hundred years old), which has again proven quite prescient. Neither of these conceptions, unfortunately, are explored in much depth, with the young Sterling keeping things fast—too fast—and furious.

Sterling’s imaginings are impressive, to be sure. They include Professor Crossbow, a mass of constantly shifting DNA; follicle mites, or little black worms, that live in wounds and eat dead cells; multisexuals, whose bloodstreams are “seething tide(s) of hormones and libido stimulants”; a highly addictive psychedelic drug called smuff; and Moses Moses, who returns from suspended animation to help the Artificial Kid in his struggle against the Cabal, a band of determinist-minded scientists who’ve ruled Reverie for three hundred years and accept no competition.

The author’s world building skills are impressive (the above is a VERY abbreviated condensation of an insanely expansive, multi-layered whole), if not quite fully developed at this point in his career. Richly detailed and convincing his imagined universe is, but it lacks the distinctiveness of the cyberpunk futuropolis of NEUROMANCER (1983), or Sterling’s positively mind-expanding later novel SCHISMATRIX (1985), which dealt with many of the same themes, but in a far more memorable and coherent manner. In its shadow THE ARTIFICIAL KID comes off as at best a warm-up.