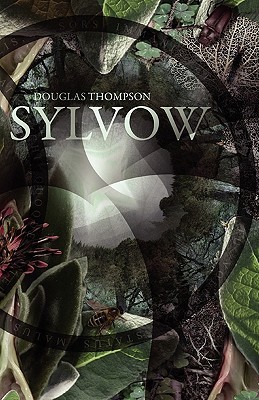

By DOUGLAS THOMPSON (Eibonvale; 2010)

By DOUGLAS THOMPSON (Eibonvale; 2010)

The environmental catastrophe genre gets an unforgettable overhaul in Douglas Thompson’s SYLVOW, which reads like an acid trip retooling of John Skipp and Craig Spector’s THE BRIDGE with hints of J.G. Ballard at his most extreme.

It unfolds as, essentially, a sustained hallucination, complete with dialogue presented in quotation-less italics (putting one in mind of warring mental ruminations) and vividly described dreams that are given scant demarcation from so-called reality. As the author makes clear toward the end of the book, “Now everybody’s nightmares had come out of the shadows, shuffled like shackled convicts from the dark folds of their brains and been granted freedom.”

The focus is on the (imaginary) British city Sylvow, located at the point where the Roman Empire began its decline, apparently due to the area’s impenetrable forests. It seems that nature has finally decided to finish the job it began so long ago, conclusively ridding the Earth of human beings (identified herein as the “biggest ecological hazards in history”) in a wildly surreal succession of catastrophes.

The highly episodic narrative centers on Claudia and Leo Vestra, siblings who made a childhood promise that he would look after the plants and she the animals. As adults the two stick to their vow, with Claudia becoming a Sylvow-based veterinarian and Leo a forest-dwelling mystic who leaves behind handwritten letters detailing his belief that nature is about to make a final apocalyptic stand.

Among other things, a tiny beating heart is found in a split-open peach and a blue eye in the center of an orange—which are but a warm-up for the insanity to come. Before long Sylvow is overrun by unidentified vegetation, giant insects and odd vegetables that drop from the sky and fasten themselves to the ground, releasing gnarled roots that strangle the town’s electrical wires and pipes. Hospital patients are burned alive by authorities after being inundated with spores that grow malignant flowers in their chests, and a girl is raped and torn apart by writhing vines.

In one particularly outrageous subplot the mayor’s pubescent son finds an enormous chestnut that forms itself into various shapes—including a brain, scrotum and vulva—that perversely correspond to the boy’s developing sexuality. The boy is ultimately done in by malevolent vegetation that springs from the chestnut and turns him into a human tree. The mayor goes mad in turn, commissioning enormous wind chimes, vast pagan-inspired bone arrangements and an environmental task force composed of men in bee masks.

Eventually Sylvow is flooded and civilization collapses. In this environment Claudia, following a failed expedition to locate Leo, has a lesbian tryst with his estranged wife Vivienne while the latter’s young son vanishes into the forest to be raised by wolves. Leo dies and his letters become sacred texts for many, while a mythic “Red Queen”—actually a local goth chick acting out her darkest fantasies—navigates a large ship through Sylvow’s newfound tributaries, raping and pillaging along the way.

Tonally this novel is all over the place, with thoughtful environmental screeds juxtaposed with episodes of scientifically questionable surrealism (anonymous phone calls from buzzing bees?) and a fair amount of bawdy humor (as when the greenery invading Vivienne’s home entwines itself into a giant penis that she, being sex-deprived, utilizes accordingly). You can be forgiven for interpreting SYLVOW as a parody of an eco-thriller, or just a rich and bizarre literary mutation that deserves to perplex and delight the widest possible audience it can attain.