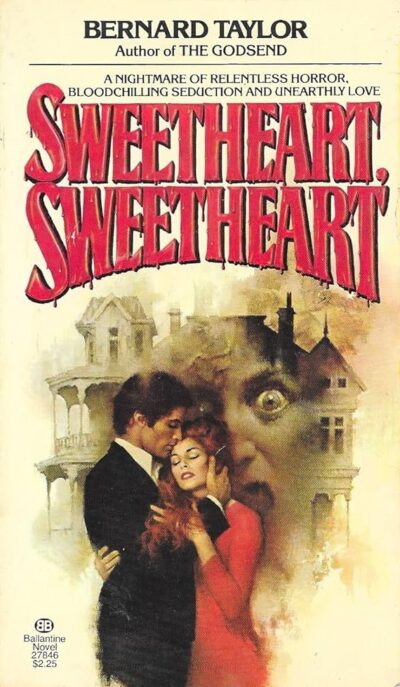

By BERNARD TAYLOR (Ballantine; 1977/79)

A novel that’s been on my radar ever since I noticed its inclusion in 100: BEST HORROR BOOKS. SWEETHEART, SWEETHEART by Bernard Taylor was selected for that 1988 tome by the late Quiet Horror booster Charles Grant, who proclaimed Taylor’s book “the best ghost story (in novel form) I have ever read, and am ever likely to read.” Having finally got around to perusing the novel, I’ll have to disagree with Grant’s raves. SWEETHEART, SWEETHEART isn’t bad by any means, but it is overlong and not entirely satisfying.

The severely drawn-out narrative certainly takes its sweet time. It’s related by the English born, New York based David Warwick, who experiences an unexpected psychic premonition relating to his estranged twin brother Colin. Still residing in the twins’ native England, Colin has just died under mysterious circumstances, followed by his wife Helen. It’s up to David to fly back to England and sort out this two-pronged mystery, a task helped by the fact that he’s been bequeathed the cottage where Colin and Helen lived.

Bernard Taylor’s major concern was evidently character building. He expends a great deal of ink on fleshing out David, his embittered father (who dubs Helen a “bitch”), his housekeeper Jean and David’s ex-girlfriend Shelagh, with whom he becomes romantically reacquainted. The mystery at the heart of the novel, like the overall narrative, takes a while to get untangled, with David navigating several false leads in his attempt at sorting out precisely how Colin and Helen met their ends. There’s also the inconvenient fact that the cottage is haunted by a malevolent female spirit.

Taylor’s manner of telling his story is intriguing. He removes many standard horror fiction trappings, most notably the expected nighttime settings, with most of the book taking place in broad daylight, and baroque prose, as the descriptions are straightforward and naturalistic. There’s also the near 400-page length, which for a 1970s horror novel was rather excessive, and the leisurely narrative construction, which I say could have been tightened up.

The intense climax, in which we finally learn the truth about Colin and Helen’s demises and the precise nature of the haunted cottage, isn’t bad. That climax is also, I’m sorry to report, not quite strong enough to justify the protracted lead-up.