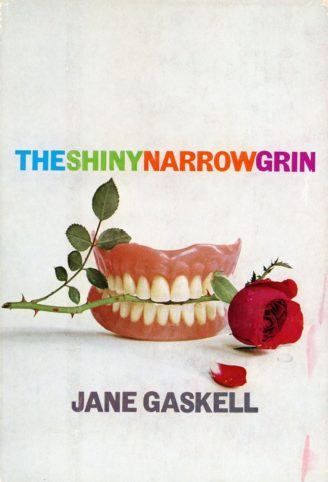

By JANE GASKELL (Hodder and Stoughton; 1964)

By JANE GASKELL (Hodder and Stoughton; 1964)

Allegedly the first-ever YA vampire romance, and so, as THE SHINY NARROW GRIN is now dubbed by many, the TWILIGHT of its day. The comparison is unfair, as this novel is infinitely more intelligent than TWILIGHT and its offshoots. Furthermore, I’d question whether THE SHINY NARROW GRIN is truly a Young Adult novel—even though it was written by a writer in her early twenties and has a teenaged girl as its protagonist—or even a proper romance.

It’s very much a product of the “Mod” scene of 1960-era London, with language and descriptions specific to the era. Reading this novel is at times akin to watching a movie whose performers speak in impenetrable accents (sample sentence: “He was at least a pep-pill taker, a boring little sniff-kid whose face was only interesting because he never got enough good Horlicks-type sleep”). Adding to the overall sense is discombobulation is an odd structure that, in a sharp reversal of traditional thriller writing, lays out most of the pertinent plot points early on and saves the defining atmosphere for the third act.

The narrative is simple enough, pivoting on Terry, a dissatisfied English teen who one night meets a strange young man on the side of a road. The meeting is a short one, but Terry is left fascinated by the pale stranger—identified as, simply, The Boy. He makes a habit of unexpectedly turning up and then just as abruptly disappearing, at one point getting into a fight and inexplicably licking the blood off the chin of his opponent. Eventually The Boy reveals his secret: he’s a centuries-old vampire who’s fallen in love with Terry, and has been surreptitiously looking after her from afar.

Terry’s attraction to The Boy is quite convincingly detailed. She finds his weirdness alluring, especially in light of the many uninspiring people in her life—a bullying teacher, an ineffectual father and a loser boyfriend she calls Fishfinger—and The Boy also arouses Terry’s budding maternal instincts (“Something in his babyhood had made him twisted and misunderstood and mixed-up…She would understand him. She could lead him back to the even more delicious paths of normality”).

The ending is a bit rushed, compressing an unwieldy plethora of information into too few pages. Yet the concluding passages are strong, leaving things, as so many British thrillers of the sixties and seventies did, on an unresolved note–which in this case seems entirely appropriate, with the author leaving it up to her adolescent heroine to choose the path of good or evil (as represented by The Boy) in the coming years.

Obviously TWILIGHT is indirectly indebted to this obscure novel, which also, in its depiction of a vampire thriving amid a hip modern milieu (as The Boy observes, “Now my clothes are right again. Now I can mingle”), foreshadows the novels of Anne Rice, THE LOST BOYS and other recent vampire media. Yet what ultimately makes THE SHINY NARROW GRIN a standout is its thoughtful and on-target exploration of the allure of vampirism. If you’re curious as to why TWILIGHT and its ilk have such a hold on teenage girls, this is the book to read.