By PETER SAXON (Paperback Library; 1967/70)

By PETER SAXON (Paperback Library; 1967/70)

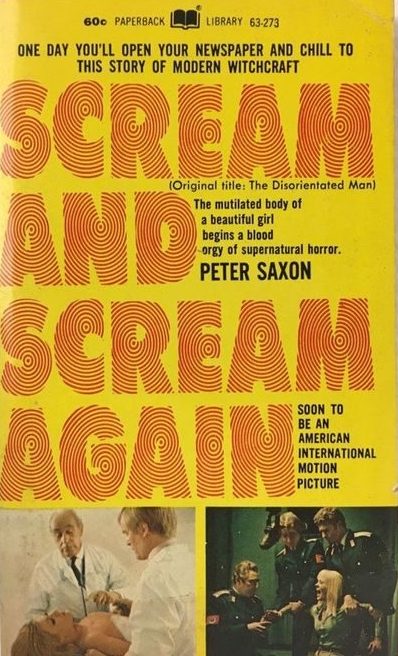

Sometimes accidental brilliance is the most irresistible sort. The British pulp item SCREAM AND SCREAM AGAIN (originally titled THE DISORIENTED MAN) proves that point adequately, it being quite brilliant in its way, although I’m not entirely sure that brilliance came about organically. Made into an interesting but unexceptional film in 1970 (see below), it’s a novel with something for everybody: mad scientists, vampires, aliens, robots, car chases, mass murder and medical experimentation, all contained in under 200 pages.

Sometimes accidental brilliance is the most irresistible sort.

The three-pronged narrative has a hint of the crazed magic of Jean Ray’s immortal MALPERTUIS in the way it constantly flirts with complete incoherency, often feeling like its story was being made up on the spot. But then, in a climactic sci fi tinged twist, the book pulls its various components together to reveal itself as a (seemingly) carefully constructed, streamlined whole.

But then, in a climactic sci fi tinged twist, the book pulls its various components together to reveal itself as a (seemingly) carefully constructed, streamlined whole.

Depicted is a German secret service agent named Konratz, who appears to enjoy his job of interrogating political detainees, which invariably involves torture, a bit too much. There’s also an investigation into a series of brutal murders (the term “serial killer” wasn’t yet a thing) whose culprit turns out to a creepy blood drinking fellow who can’t seem to be killed. Then there’s Ken Sparten, a young athlete who finds himself immobilized in a hospital bed, where he constantly awakens with one less body part. All three strands involve odd physical attributes, such as wounds that heal themselves and superhuman strength, as well as strange elements, such as a suspicious vat of acid, that aren’t initially explained.

The author was Stephen D. Frances, writing as “Peter Saxon” (one of several “floating pseudonyms” utilized in 1960s pulp fiction). Frances appears to have had very little in mind outside the 1960s pulp novel perimeters, as indicated by the too-short 158 page length, prose that often veers toward the purple end of the spectrum (“But now it was night and the Recreation Ground was an enormous pool of darkness in which horror and menace lurked”) and a sensation-heavy narrative That narrative appears to have been conceived primarily as a box-checking exercise, with Frances trying to include as many exploitable elements as he possibly could.

Again, though, there is a magic to this crazy-quilt mixture, marked as it is by a wealth of manic invention and sheer audacity. The book’s American publishers don’t appear to have known what to do with it, as evinced by the thoroughly misleading cover blurb promising a “story of modern witchcraft” and an “orgy of supernatural horror.” Neither of those things are present in SCREAM AND SCREAM AGAIN, whose true orientation is far more esoteric and intriguing. The author’s level of ambition may be difficult to gauge, but his achievement isn’t.