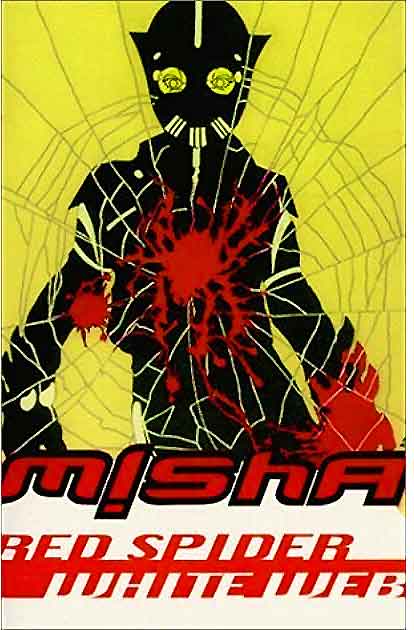

By MISHA (Morrigan Publications; 1990)

By MISHA (Morrigan Publications; 1990)

Here we have what is undoubtedly the most widely discussed yet least read book of the cyberpunk cycle. RED SPIDER, WHITE WEB, the first and thus far only novel by the Native American poet Misha (Nogha), was initially published as a limited edition hardcover by Morrigan Publications in 1990, followed by a trade paperback edition by Wordcraft a decade later. Both are now long out of print, and second-hand copies aren’t too readily available (as you might guess, I didn’t have an easy time getting ahold of one myself).

…the most widely discussed yet least read book of the cyberpunk cycle

The novel’s scarcity may be for the best, as it’s not an easy read. One critic likened it to “Arthur Rimbaud writing cyberpunk,” and I’d say that’s a valid summation. Dense, poetic and often downright oblique, Misha’s prose requires close attention on the part of the reader, and, as with most cyberpunk lit, is concerned primarily with surface detail. To make things even less reader-friendly, that detail is extremely bleak and gritty (wind, for instance, is described as “sulphur” and “razory”), a far cry from the techno-romanticism of William Gibson and Bruce Sterling (although it isn’t too far removed from the streetwise cyberpunk novels, such as BLACK GLASS, of John Shirley, who mentored Misha).

Dense, poetic and often downright oblique, Misha’s prose requires close attention on the part of the reader, and, as with most cyberpunk lit, is concerned primarily with surface detail.

The nominal setting is Mickey-san, a city in which all crime has been eliminated and its wealthy citizenry spend their days ensconced in virtual reality paradises. It’s in the catacombs underneath Mickey-San where most of the action occurs, in Dogton, a slum populated by “the dung of life.” Among its ranks is Kumo, a young woman artist who has by necessity become “twice as savage as any of the male artists she hung out with.” There’s also Tommy Uchida, a cybernetically enhanced nut with a god complex who works as a repairman in Mickey-San, where he indulges his outlaw whims by mischievously sabotaging its citizens’ virtual environs.

Kumo, after much harassment at the hands of robotic policemen known as the Navvys, is herself given a fair amount of bodily enhancements, though not voluntarily. And as if all that weren’t enough, a murderer is loose in Dogton who appears to be targeting artists.

The novel is impressively rendered and (for the attentive reader) compelling, but it has problems. Many interesting concepts are breached, such as a horrific detention center/concentration camp known as the Bell Factory that’s referenced throughout the book but whose interior is never described (apparently a sequel is in the works that promises to fill us in). Another, more fundamental issue is with the fact that, simply, its protagonist was wrongly chosen. It’s Tommy Uchida who should have taken the lead, he being a complex and fascinating creation, while Kumo (doubtless an autobiographical stand-in for the author) exists, it seems, primarily to be victimized.

The novel is impressively rendered and (for the attentive reader) compelling, but it has problems.