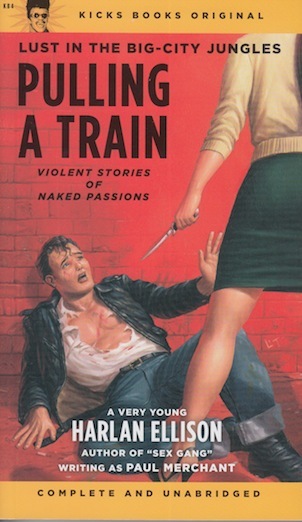

By HARLAN ELLISON (Kicks Books; 2012)

By HARLAN ELLISON (Kicks Books; 2012)

Another “new” collection by Harlan Ellison consisting of (very) old stories. Here, as in his other recent collections ROUGH BEASTS and HONORABLE WHOREDOM AT A PENNY A WORD, Ellison collects several of his stories from the late 1950s and early 60s, in this case sleazy Jim Thompson-esque pulp written for the men’s magazines of the era. (It was followed, incidentally, by a second collection of like-minded tales entitled GETTING IN THE WIND, but of the two books PULLING A TRAIN is definitely the one to read.)

Gut-level sex and violence are the order of the day here, as exemplified by “Sex Gang,” the first and longest of PULLING A TRAIN’S six stories. Its opening sentence, “Derek hadn’t wanted to rape the girl,” adequately sets the tone for an account of a petty thief drawn into the orbit of a ruthless girl gang. Throughout, the emphasis is on R-rated carnality and bloodletting in a big city hellscape that was evidently inspired by Ellison’s real-life experiences with street gangs (as chronicled in MEMOS FROM PURGATORY).

“Nedra at f:5.6” is about a cheesecake photographer who becomes besotted with a seductive woman whose true nature may be more than human. Of a somewhat lighter hue is “The Bohemia of Arthur Archer,” in which a straight-laced college boy attempts to impress a bohemian hottie by transforming himself into a beatnik, with decidedly unpredictable results.

In “Jeanie with the Bedroom Eyes” a bachelor becomes determined to seduce a department store model, leading to the “most revolutionary window display ever conceived.” “Both Ends of the Candle” concerns a randy young man whose insatiable sex drive lands him in a most unique predicament: he becomes caught between a sex-crazed mother and daughter, who use him as an erotic plaything (poor guy!). The final story is “A Girl Named Poison,” which brings back the grit and grime of “Sex Gang” in its depiction of revenge and star-crossed love amid a brutal gangland milieu.

These stories may lack the mature worldviews and ruminations on the human condition that typify Harlan Ellison’s later fiction, but taken purely as lurid, pulpy entertainment they excel. In true pulp fashion, these tales are lean, uncluttered and heavy on the nastiness, with a time-capsule fascination that stems from the fact that all are quintessential products of their era.