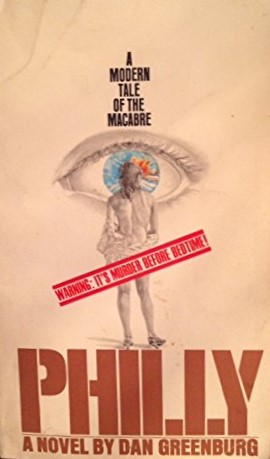

By DAN GREENBURG (Bantam; 1969/71)

By DAN GREENBURG (Bantam; 1969/71)

If you know this book at all it’s most likely as the source for the hit teen sex comedy PRIVATE LESSONS (1981). What’s interesting about PHILLY, which was transposed to the screen with a fair amount of fidelity (only the ending is truly different) by its author, is that it’s diametrically opposed to the flick tonally, purporting to spin a “Modern Tale of the Macabre.”

…the source for the hit teen sex comedy PRIVATE LESSONS (1981)

Such a cinematic tonal shift isn’t entirely unheard-of. In 2007 author Jay Bonansinga adapted his horror story “Stash” into a similarly monikered independent film that, as with PRIVATE LESSONS, turned the material into a comedy. That transposition, unsurprisingly, resulted in a film that didn’t work, whereas with PHILLY the effect was reversed: the material actually works better in comedic form, with the source novel (initially serialized in Man’s Magazine) feeling misconceived.

Private Lessons (1981)

It’s about Philly, the 14-year-old son of a rich widower who leaves his son alone for the summer. Charged with looking after Philly are a thirtyish governess he knows as Miss Mallow, and a chauffeur identified as “Lester the Fruit” (no, this book does not follow the dictates of modern political correctness). The former behaves quite inappropriately around the hormone-addled Philly, and eventually deflowers him outright.

Then one night Philly impulsively proposes marriage and Miss Mallow ridicules the idea. He’s pissed and, after fantasizing at some length about killing her, discovers her seemingly dead body. Thus he’s left alone in his father’s mansion with the hated Lester the Fruit—whose consultations, as you might guess, aren’t too helpful.

Reading this book I was reminded of Stanley Kubrick’s recollections of scripting DR. STRANGELOVE (1964), an initially serious depiction of the possibility of nuclear warfare that became a comedy due to the sheer ridiculousness of the story Kubrick was trying to tell. In PHILLY it’s likewise difficult to ignore the silliness inherent in the narrative and dialogue (upon catching Philly watching her strip early on in the book, Miss Mallow asks “if you wanted so much to watch me undress, why didn’t you tell me?”), which only grow more outrageous as the book advances, and a litany of wild twists, and twists-on-twists, are offered up.

Beyond that PHILLY is a fast, easy read. If not for the R-rated subject matter it could qualify as a children’s book (a type of publication Greenburg had already turned out), and a darkly funny one.