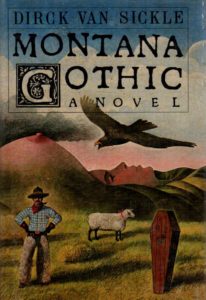

By DIRCK VAN SICKLE (HARCOURT BRACE JANOVICH; 1979)

By DIRCK VAN SICKLE (HARCOURT BRACE JANOVICH; 1979)

A fascinating, poetic and macabre novel that may be a masterpiece–and if it isn’t, it comes damn close. In MONTANA GOTHIC author Dirck Van Sickle dramatizes the passing of the Old West, specifically Montana, in a distinctly eerie, horrific fashion.

The narrative consists of five more-or-less self-contained stories, connected by a few recurring characters and a chronology that spans the early 1900s to the “present day” (the late 1970s). In Van Sickle’s hands the ever-present Montana scenery becomes a dark, forbidding psychoscape where “the vast carpets of wheat and sugar beets become a threadbare linoleum when yearly stomped to death by an unmotherly nature.”

It begins in fittingly gothic fashion, with Deke, a heartbroken man, arriving in the town of Citadel to take over for its deceased undertaker. Unfortunately Deke’s predecessor performed decidedly gruesome acts on his subjects, which Deke doesn’t know about…but the townspeople do! Loneliness and isolation are the inevitable result. Not even the love of a naive young woman can improve Deke’s lot, as, inevitably, Deke’s newfound lover dies shortly after she appears.

Deke’s experiences effectively set the tone for the rest of the book, which continues with “Winter Calf,” in which the young, cynical Anthony finds himself trapped with Boss James, a doddering old fool (and supporting character from the previous story). In “Legacy” Anthony unwisely casts his lot with Melinda, the mentally deficient offspring of Edward, a tyrannical patriarch who rules his household with an iron fist. Over the course of “Legacy” and the succeeding “Bequeathal” we learn more about Edward’s life, which has been tainted by the death of his mother, after whose passing “the fear blossomed and spread like black vines through Edward’s mind, and he survived, but just barely, by making sure that nothing further was changed, nothing further taken away.” But his carefully wrought existence is brought crashing down by his disturbed daughter’s unexpectedly murderous actions.

The final story, “Mavis,” is the weakest. While the writing in this tale of an old-fashioned gunslinger brought down by a modern world he doesn’t understand is definitely up to the high standards set by the rest of the book, it spells out the overriding themes a bit too blatantly. Mavis’ origins are left hazy; we can only assume he’s somehow traveled through time, an explanation in direct contrast to the haunting air of near-unconscious mystery that pervades the rest of the book.

It’s that sense of brooding uncertainty that gives MONTANA GOTHIC its kick, a pungent air of fear and dislocation that passes virus-like from character to character. The prose is gorgeously literate and expansive in the manner of classic horror scribes ranging from Poe to Maupassant, creating an atmospheric evocation of the American Northwest as a landscape of dreams–or nightmares.