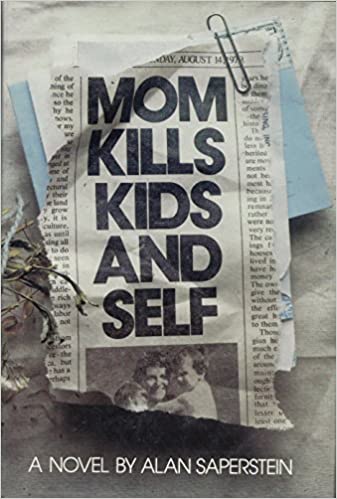

By ALAN SAPERSTEIN (Macmillan; 1979)

By ALAN SAPERSTEIN (Macmillan; 1979)

That title tells the story of this odd and troubling late seventies artifact, a somewhat experimental, psychologically based account of grief and madness. It is, in short, the very opposite of an easy or enjoyable read.

Spanning a single weekend, it begins on Friday evening with the first person protagonist, a more-or-less normal suburbanite, arriving home from work to find the corpses of his wife and two young children laid out in his living room. Based on the condition of the bodies—one kid’s head is bashed in, the other has strangulation marks on his neck and the woman’s wrists are slashed—the man determines that his wife murdered the children and then committed suicide.

What follows is a period of near-hysterical denial, with the protagonist lavishing unusual attention on getting dressed and mowing the lawn the following morning, with nary a thought about his dead wife and kids outside a lingering suspicion that “Something wasn’t right.” He heads to his Manhattan office where he works as a scientific researcher. There he calls in one of his previous subjects, Mrs. P., because of the answers she gave to questions about wifely devotion. A couple of her statements in particular linger: “Women don’t have orgasms. They just satisfy their husbands” and “Sometimes thinking too much gets you nowhere but into trouble.” Clearly she’s embraced a subservient role, which the protagonist’s wife evidently didn’t. Unfortunately the ensuing encounter, during which the guy ransacks his workplace in a fit of grief and all-but rapes Mrs. P., offers nothing in the way of reassurance.

It’s on Sunday that the man is forced to confront the reality of his situation, and in the process goes full-tilt bonkers. Things go from bleak to downright macabre in this portion of the book, which sees the protagonist acknowledging his failure as a husband and leads to an act of implied necrophilia.

In MOM KILLS KIDS AND SELF Alan Saperstein has created a novel that mirrors the inner state of the protagonist in every respect: it’s unpleasant, tedious, depressing and often downright ugly. It’s also entirely convincing in its dissection of grief-born insanity, being a novel I admire greatly, even if I don’t much like it.