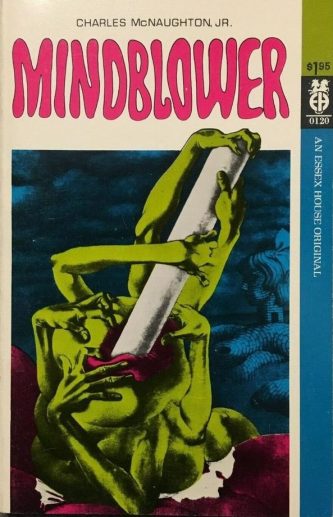

By CHARLES McNAUGHTON, JR. (Essex House; 1969)

By CHARLES McNAUGHTON, JR. (Essex House; 1969)

I suppose I should go easy on this one. It was the first novel by a twenty year old author, written for the late counterculture infused smut outfit Essex House. MINDBLOWER is far and away the rarest Essex House book; it’s not included in an otherwise exhaustive blog posting on the subject at Paris Olympia Press, and even Maxim Jakubowski, whose 1978 article “Essex House: The Rise and Fall of Speculative Erotica” is widely viewed as the definitive Essex history, clearly hasn’t read it (with his entry on the book consisting solely of an out-of-context quote from Philip Jose Farmer’s afterward).

As it happens, MINDBLOWER is very much of a piece with another incredibly scarce Essex title, GROPIE by Barry Luck. The authors in both cases haven’t been heard from much in the years since, and their novels each consist, in lieu of conventional narratives, of a succession of picturesque adventures experienced by turned-on protagonists. McNaughton adds a science fiction touch in the form of a wonder drug known as the Mighty Quinn that comes into play in the novel’s final third, in which said drug is administered to the protagonist and then mixed into the water supply of San Francisco, leading to the “Great Haight-Ashbury Dog-Shit Orgy” (so named because the participants ecstatically smear canine excrement on their bodies).

Before then we’re introduced to Jack Flasher, a Haight Street based hippie, and Phaedra, a busty chick to whom Jack introduces himself with the line “Hello, are you trippin’ too?” Drafted in freeform prose that reads like some unholy mash-up of William Burroughs and Terry Southern, the book provides copious amounts of minutely detailed sex, at least two equally detailed acid trips and a lot of miscellaneous narrative detours. Among the latter are transcriptions of nonsensical prose poetry Jack writes, an encounter with a crazed auto mechanic who kills and then impersonates a policeman, another with a bunch of dildo hat wearing geriatrics, and another with a cadre of tripped-out dwarves who set in motion the apocalyptic climax.

It’s all very silly, and not helped at all by an uncertain tone the alternates haphazardly between satire and profundity. In fairness, that latter complaint may have been the fault of Essex House’s overseers, who reportedly disdained comedy of any sort (their mantra, according to Essex author Jane Gallion, was “Ya can’t laugh and keep a hard-on”) and were known to take a heavy editorial hand. Not that such things matter much in the case of MINDBLOWER, as this impossible-to-find book is one that, frankly, very few people will ever read.