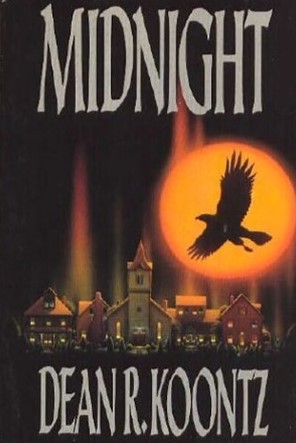

By DEAN KOONTZ (Berkley; 1988)

By DEAN KOONTZ (Berkley; 1988)

A pretty standard Dean Koontz programmer with all the elements that marked his eighties-era novels: an absurdly virtuous hero, a sappy romance, a happy ending and a highly preachy, self-righteous air (an element that’s run rampant in Koontz’s post-eighties novels). MIDNIGHT may more overtly horrific than many Dean Koontz novels, but its preachiness and sentimentality mark it out as quintessentially Koontz.

The setting is the California seaside community Moonlight Cove, where an unholy experiment is being conducted. The experiment’s ringleader is Thomas Shaddack, a power-mad visionary looking to convert humankind into apparently superior “New People.” He does this with a specially created serum that when injected into people succeeds only in turning them into murderous beasts.

It isn’t long before nearly the entire community has been converted, with only four people managing to withstand the insanity: the novel’s hero Sam Booker, an undercover FBI agent with a rebellious teenage son; Chrissie Foster, a plucky eleven year old attempting to deal with the fact that her parents have become monsters; Sam’s designated romantic partner Tessa Lockland, a documentary filmmaker investigating the death of her sister Janice, who allegedly committed suicide (the opening chapter, in which Janice is pursued and thrown off a cliff by a pack of dog-like men, proves otherwise); and Harry Talbot, a wheelchair-bound Nam vet who spends his days spying on his neighbors with binoculars.

Opening the novel with Chrissie running from her converted parents was a good move on Koontz’s part, creating an action-intensive counterpoint to the dull scene setting and character development of the early chapters. Otherwise, however, the book is quite standard in its development, driven by gory set pieces (the best of which involves Chrissie and a seemingly kindly priest) and breakneck action, whose overall effect is lessened considerably by the vastly bloated 470 page length.

As is his practice, Koontz, an avowed opponent of obscurantism in fiction, is careful to telegraph his story’s themes and overall message. One character provides a detailed comparison of the actions of Shaddack and Dr. Moreau, and another pontificates repeatedly on the importance of responsibility in one’s thoughts and actions. That last point is underlined by the final scene, which (semi-spoiler alert!) involves not Shaddack and the New People but a confrontation between Booker and his punk son. It’s here that the preachiness I mentioned above really comes into play.

For good measure, Koontz includes a nonfiction afterward urging readers to donate to a California-based service dog organization, apparently “a rare opportunity to make a real difference in the world.” As a dog lover I’ll give Koontz a nod for that sentiment, but it feels out of place in an escapist entertainment that’s mildly diverting at best.