By ED PINSENT (Eibonvale; 2010)

By ED PINSENT (Eibonvale; 2010)

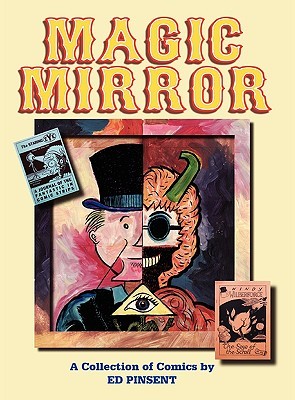

A worthy, if frustratingly little known, addition to the underground comics scene, MAGIC MIRROR collects 44 1980s and 90s era comic strips by England’s Ed Pinsent. As presented here, Pinsent’s work, taken from publications like THE STARING EYE, HONK!, KNOCKABOUT COMICS and GAG!, fits in reasonably well with the underground aesthetic, given that his drawings are often deceptively childlike in appearance, and have a concentration on death and destruction. Where these comics differ from most underground strips is in their literacy and intelligence, with the cheap shocks and gross-out excess generally associated with the “comix” world played down severely.

…drawings are often deceptively childlike in appearance, and have a concentration on death and destruction.

Surrealism is a guiding principle of Pinsent’s art, as is (according to the biographical notes included in the book’s final pages) fantastic literature, with Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino exerting a much greater influence than R. Crumb or S. Clay Wilson. Other evident influences were the comic strips of past decades, with the work of long-dead masters of the form like Carl Barks aped quite brilliantly in Pinsent’s seemingly unsophisticated drawings, which when studied closely are revealed to be quite sophisticated indeed.

“For a long time I have tended to resist explanations and solutions to my stories, but I do realize that their meaning is often far from clear, and some readers remain baffled.”

Typical of his work is “The Recolte,” which according to the notes is “actually a love story” that’s “disguised as a dystopian science fiction tale.” It’s set in a postapocalyptic landscape where a scientist captures a bird that constantly mutates, and, after getting bitten by the thing, the scientist follows suit. Don’t expect a conventional, or entirely coherent, denouement, as that’s not how Pinsent’s narratives work (his notes claim that in the tale’s conclusion the bird “appears to have dissolved its very molecules into the atmosphere, becoming part of the very weather system that created it”). As he admits, “For a long time I have tended to resist explanations and solutions to my stories, but I do realize that their meaning is often far from clear, and some readers remain baffled.” True, but that obtuseness, in the manner of the artistic influences Pinsent mentions in his notes (which in addition to Borges, Calvino and Barks include William Golding, Francis Bacon, THE SHOUT, M.R. James, THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT and Frankie Goes to Hollywood) grows mesmerizing once the reader adjusts to the stories’ surreal rhythms and imaginative fecundity.

Standouts include “The 7 Faces of Manley Ville,” a mind-boggler about a lovesick man whose “faces” are actually objects, such as an exploding box, a snake emerging from a jar and a multi-tongued mouth, that appear on his neck (in place of a head) to denote his current mood; “Sounds of the Past,” in which a man is able to record sounds from impossibly distant time periods, and eventually channels the voice of God “speaking the very word that had brought the earth into being”; “My Master’s Lame,” told from the point of view of a dog tasked with hauling around his crippled human master, all the while dreaming of killing the man; and “Alien Nation,” one of the most overtly experimental offerings, utilizing a method similar to the cut-up writing technique popularized by William Burroughs in relating the account of a young man’s encounter with a UFO that’s told three times, with each telling juxtaposing the art and captions in different ways.

…the account of a young man’s encounter with a UFO that’s told three times, with each telling juxtaposing the art and captions in different ways.

The book’s second half is devoted to comic strips featuring Pinsent’s most famous creation: Windy Wilberforce, a character who received his own self-titled, multi-volume comic. He’s a rotund scholar who investigates various non-human environs, including, in “Ocean Lands” and “Windy and the Whitefish,” the bottom of the sea, and, in “The Fortress of Language,” a unique repository of arcane knowledge situated in a vast desert. Windy’s—and the book’s—lengthiest and most ambitious adventure occurs in “The Saga of the Scroll.” Six years in the making, this anti-epic utilizes a variety of drawing styles in an insanely wide-ranging saga that involves an ancient scroll, a trip through the cosmos, talking animals, plants that grow numerical digits, humans harvested for insect food, a giant man whose head grows beneath his shoulders and the birth of the antichrist. Yes, it’s that kind of book.