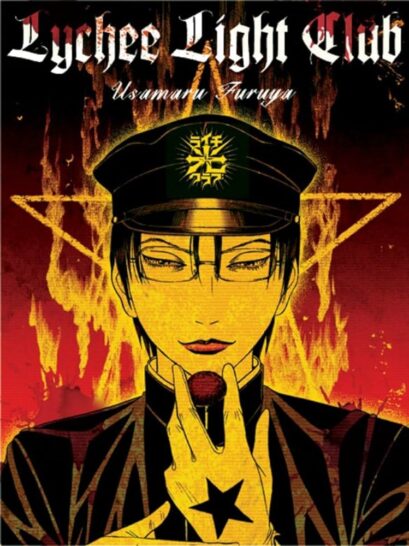

By USAMARU FURUYA (Vertical; 2005-06/2011)

You can be forgiven for thinking this manga one-shot, involving perversion and psychosis amid a group of middle schoolers, is an example of Japan’s ero-guro (erotic grotesque nonsense) genre. It would certainly appear so, especially given that Usamaru Furuya’s LYCHEE LIGHT CLUB was inspired by a 1985 play performed by the Tokyo Grand Guignol (in which Furuka was a direct participant, as was guro master Suehiro Maruo). It is, however, a seinen, or young adult oriented, manga.

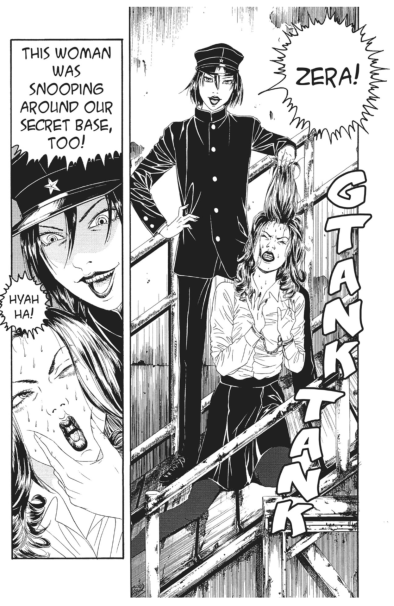

The early pages aren’t too promising from a conceptual standpoint, depicting the eponymous Light Club, a group of dour black suit-clad young men, communing in an industrial warehouse. Led by the sociopathic Zera, these youth-obsessed freaks have kidnapped two teachers they subject to horrific torture that leaves one of the victims without eyes and the other with her large intestine used as a scarf. It all seems like a shallow exercise in grossness-for-grossness’ sake, but as the story advances it reveals itself as a nuanced and provocative take on some pertinent themes (namely the dangers of conformity and the deadly allure of fascism), helped along by boldly stylized and symmetric black-and-white artwork.

As a bevy of artfully placed flashbacks make clear, Zera was an outcast who seized control of the Light Club, a benign gathering that was transformed into an overtly authoritarian cult. Zera’s latest, and grandest, gambit is the creation of Lychee, a robot powered by lychee fruit that’s designed to do something none of the Light Clubbers can: get girls. This nets a doe-eyed young woman who the club members chain up and christen Number One. She enraptures both Zera and Lychee, with the latter’s actions and feelings becoming increasingly humanistic—more so, in fact, than those of his human overseers.

Not that the Light Club members, for all their rigidness and uniformity, are without human foibles. The group is overcome by infighting as Zera becomes increasingly insecure and plain crazy, and the story’s gay overtones are made progressively more explicit (yes, these guys are all drawn to Number One, but seem far more enamored with each other). Note that all the male protagonists are made to look overtly feminine, and the copious depictions of erect penises that bely the young adult label.

So too the uber-gory final panels, in which the grand guignol designation really makes itself apparent. Furuya’s mixture of artful nuance and gory excess is more harmonious than you might expect, resulting in a concoction that’s challenging, disgusting, confounding and like nothing else.