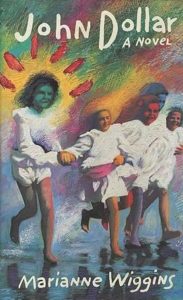

By MARIANNE WIGGINS (Harper & Row; 1989)

By MARIANNE WIGGINS (Harper & Row; 1989)

Although I’m sure its author and publisher would be loath to admit it, this highly literary historical reverie is very much a horror novel. The subject? A gaggle of English schoolgirls, together with a crippled sailor who gives the novel its name, shipwrecked on an island in 1918, where they endure hunger, fatigue, mosquitoes, savage man hunters, carnivorous ants and, inevitably, madness. Yes, most of the girls die, and yes, the specter of cannibalism does rear its ugly head.

Keep in mind, though, that the above covers only the book’s second half. The fist is largely concentrated on the character of Charlotte, the girls’ free-spirited headmistress, an irrepressible convention breaker on a jaunt through the Orient, where she meets the sailor John Dollar during a dreamlike nocturnal swim. Naturally I found Charlotte’s exploits far less compelling than the horrific business of the book’s second half, and neither was I terribly enchanted by author Marianne Wiggins’s deeply affected present tense prose (“Every step she takes at this depth is a formulation of an if then, a hedonic calculus—across the calcified anatomy of coral her little toes appraise the price of pain against the gain of pleasure.”)

I realize this is the sort of book literary critics drool over (apparently it’s the type of writing that, according to a back-cover blurb, “can make you laugh aloud, while somewhere inside, you are crying”), but it definitely ain’t my cup of tea. For that matter, I don’t quite understand why the author devotes so much time to Charlotte in the book’s first half, as the character spends the majority of the second offstage.

In any event, the book catches fire once Charlotte and the kids are packed into the John Dollar-manned ship that takes them to meet their untimely destiny. The English colonels, it seems, are in search of obscure lands they can claim as part of the British Empire. But a tidal wave hits, killing off everybody but the now-paralyzed John Dollar and the schoolgirls. The prose here is just as affected as that of the first half (“…everything the ritual contained became symbolic of its former self, symbolic of its former symbol like a love that calls itself a love when it’s grown loveless”), but the sheer relentlessness of the story kept me going. Furthermore, Wiggins’ prose does an excellent job conveying the increasingly hallucinatory mindsets of her malnourished subjects. As might be expected, though, Wiggins refuses to provide a cut-and-dried ending, forcing the reader to go back and reread the opening pages (chapter one being a brief remembrance of the events on the island) to find out what happens.

LORD OF THE FLIES was clearly an influence on this book, as was HEART OF DARKNESS. The social dynamics of children stranded on an island without adults call to mind the former book, while the story’s underlying political implications mirror the latter. Just as Colonel Kurtz’s descent into savagery was intended to symbolize the decline of the British Empire, so it seems do Marianne Wiggins’ schoolgirls, whose ill-fated mission is in service of the British crown. But then, I don’t remember LORD OF THE FLIES or HEART OF DARKNESS being nearly as pretentious as JOHN DOLLAR.