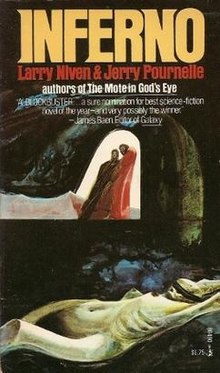

By LARRY NIVEN, JERRY POURNELLE (Pocket; 1976)

By LARRY NIVEN, JERRY POURNELLE (Pocket; 1976)

Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle are known primarily for “hard” sci-fi novels like LUCIFER’S HAMMER and FOOTFALL. I’m not too into that sort of thing, but INFERNO is something else entirely: a sprightly, surreal and totally captivating fantasy with a daring take on the inferno as imagined by Dante Alighieri.

Dante’s INFERNO, for those who don’t know, was the opening portion of the DIVINE COMEDY (1308-1321), a three-part epic poem about Dante’s exploits in the afterlife (with the succeeding portions focused on Purgatory and Heaven). Told in the first person, Dante’s INFERNO consists of his journey through the nine circles of Hell, guided by the Roman poet Virgil.

In Niven and Pournelle’s INFERNO the protagonist is science fiction novelist Allen Carpentier, who during a party falls eight stories and comes to in Hell. More specifically, he finds himself trapped inside a bronze bottle, located at the Vestibule to Hell. But then he’s poured out by a burly European-accented individual named Benito, who ends up playing Virgil to Carpentier’s Dante as the two traverse the nine circles of Hell. They’re made witness to all manner of tortures along the way, and pick up (and discard) travel companions that include a space shuttle pilot named Corbett and none other than Billy the Kid. Their journey encompasses a flight over the infernal city of Dis in a homemade glider, a wade through a lake of boiling blood and a rumbling ride across a flaming desert in a self driving car.

As a pure adventure story this book is virtually impeccable. It suffers only from Carpentier’s distracting interior monologue that periodically interrupts the action (he initially thinks he’s in some kind of sci-fi theme park called Infernoland); introspection is evidently not something Niven and Pournelle do especially well. Fans of more up-to-date fictional treatments of the inferno like Jeffrey Thomas’ LETTERS FROM HADES and Wrath James White and Monica O’Rourke’s POISONING EROS will likely chafe at the rather perfunctory descriptions and lack of X-rated detail, but that at least makes sense from a character standpoint. The tale, after all, is told from Carpentier’s weary, curmudgeonly viewpoint, which is anything but soulful and contemplative (another reason the introspective asides don’t work).

It’s difficult to remain cross with this book for too long, in any event, as it’s such a blast of imaginative nastiness. Many surprises are in store for Carpentier and the reader, including Benito’s real-world identity (his last name is withheld until near the end) and the final revelation of the true purpose of Hell. The latter is pure speculation on the parts of Niven and Pournelle (and decidedly blasphemous speculation at that) but nonetheless makes perfect sense.

FYI, the authors crafted a sequel to this book, ESCAPE FROM HELL, in 2009.