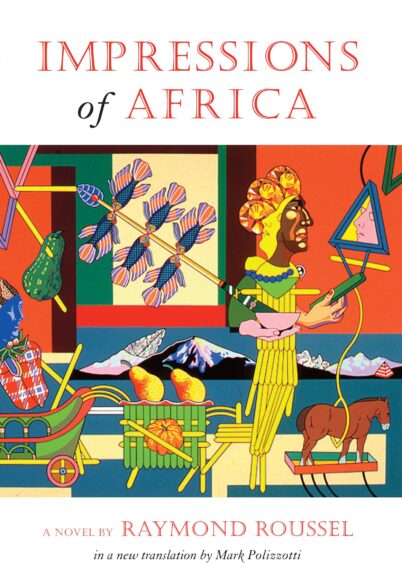

By RAYMOND ROUSSEL (Dalkey Archive Press; 1910/2011)

Raymond Roussel may well be the strangest writer of all time. An eccentric Frenchman who lived and wrote around the time of the surrealists (but never officially joined the party), Roussel created a distinctive fictional world unlike that of anybody else. IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA, his first prose novel (it was preceded by LA DOUBLURE, written entirely in verse), was inspired by a trip Roussel took to Africa, during which he reportedly never left his hotel room.

IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA’s initial self-published 1910 manuscript was apparently filled with elaborate wordplay that can’t be expressed in English. The translation by Mark Polizzotti, however, is quite strong, and the events described by Roussel, contained in a wholly bizarre three-tiered structure, are more than enough to sustain the book on their own.

It begins with some highly eccentric performances and inventions, put on to celebrate the coronation of an African prince. There’s a man who literally sings out of both sides of his mouth, a boy who uses rodent blood to glue himself to a board that’s carried off by a large bird, a segmented worm that plays a stringed instrument by lifting parts of its body to drip strategically aimed drops of water on the strings, grapes with tiny paintings visible inside them and a performance of the final scene of ROMEO AND JULIET, complete with Biblically inspired hallucinations.

Halfway through the book the narrator reminisces about what brought him and his companions to this point. It turns out they were passengers on a ship that crashed off the coast of Africa, where they were taken hostage by a corrupt monarch in perpetual combat with his twin brother, himself a monarch (the full story of their rivalry is far, far too complex to detail here). Seeing as the hostages were comprised of actors, scientists and artists, they were obliged to come up with novel ways to impress the young prince upon his coronation and, as was made clear in the opening passages, nailed the assignment.

Roussell goes on to fill in the backstories of the various contraptions and performances described in the first half, which involve the discovery of the original version of ROMEO AND JULIET (quite different from the one we know), the retrieval of weird critters and vegetation from the depths of the ocean, the implantation of tiny paintings into the seeds of grapes, etc. Eventually the narrative returns to the present, with all the prisoners freed and the ending a happy one.

This book, I’ll have to admit, is often difficult to read. Roussell’s prose is simple and uncluttered, but lacking many attributes we’ve come to expect from “good” fiction; the whole thing is related secondhand, in a calm and unruffled monologue with nothing in the way of conventional action, characterization or symbolic heft. Raymond Roussel is, in short, an acquired taste, but once the reader adjusts it’s impossible not to be enchanted by the ceaseless flood of imagination on display. After reading this novel you may even be ready for Roussel’s even-wilder follow-up LOCUS SOLUS, which takes all the good things about IMPRESSIONS OF AFRICA and amplifies them.

See Also: LOCUS SOLUS