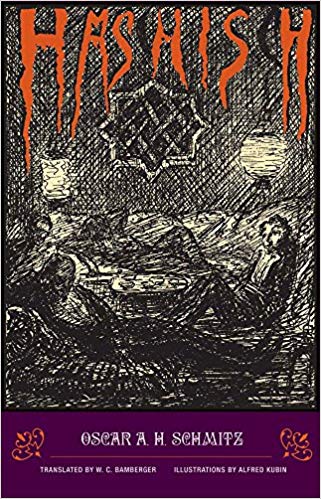

By OSCAR A.H. SCHMITZ (Wakefield Press; 1902/2018)

By OSCAR A.H. SCHMITZ (Wakefield Press; 1902/2018)

Germany’s premiere example of “drug writing,” 1902’s HASHISH by Oscar A.H. Schmitz appears here in its first ever English translation. An elegant stew of Satanism, lust, madness, murder, blasphemy and (of course) drug use, it’s about as decadent as decadent gets, although such fare was rarely presented with the poetic erudition provided by Mr. Schmitz, whose characters are given to elegant soliloquies about their vices in conjunction with the highly florid descriptions.

A nonfiction afterward by James J. Conway provides some much-needed biographical info. We learn that Mr. Schmitz spent a great deal of time in 1890s Paris, when decadence and perversity were all the rage. A few years later he befriended a young Gustav Meyrink and helped get his early writings published. HASHISH, published in 1902, was Schmitz’s first work of prose fiction, and showcased the fruits of his time in Paris.

HASHISH consists of seven interrelated tales, beginning with “The Hashish Club.” Imbibing the titular substance in this club (inspired by an actual Parisian locale), the narrator finds himself assuming various guises in the following tales, starting with “The Devil’s Lover.” Here a perverse love affair is carried out entirely in darkness, while in “A Night in the Eighteenth Century” a posh dinner party degenerates into an orgy of erotic bloodlust after the guests are given drugged wine. Necrophilia is the subject of “Carnival,” while in “The Sin Against the Holy Ghost” a gang of punks decide to defile a chaste young woman, and in “The Message” a man is seduced by an incubus. The book concludes with “Smugglers’ Pass,” a “Pre-Revolutionary Episode from the Private Notes of A Journalist.” An odd and rather puzzling appendage, it’s light and romantic in temperament, and so quite divergent from the rest of the book.

It all adds up to pleasing bit of early Twentieth Century outrage. The author may be a bit too eager to shock, an attribute he shares with the Parisian provocateurs J.K. Huysmans and Jean Lorrain—both of whom are reflected, if not shamelessly imitated, in these pages.

Obviously HASHISH is no longer as outrageous as it once seemed, but Schmitz’s irrepressible envelope-pushing spirit remains quite potent. Adding to the decadence are illustrations by the skilled horror/fantasy draftsman Alfred Kubin (the author’s brother in law), whose sketchy artwork essentially defines the early Twentieth Century gothic imagination.