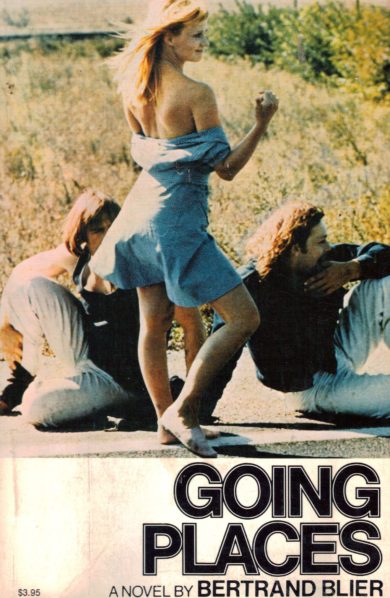

By BERTRAND BLIER (Lippincott; 1972/74)

It’s rare to find a novel—any novel—containing a perfect opening sentence. This, the first and only English translation of Bertrand Blier’s LES VALSEUSES, a.k.a. GOING PLACES, a bestseller in France that inspired the Blier directed 1974 film of the same name, is just such a book, with an opening line—“We’re real fuckheads”—that perfectly encapsulates the attitudes and aspirations of its protagonists.

The GOING PLACES film, which seems destined to be the form in which this material is best known, is one about which I’ve never quite made up my mind. A stylishly visualized comedy that revels in ugliness and amorality, it may well be the irredeemable shock-fest its detractors like to proclaim it, or perhaps it’s a society-bashing masterpiece. That dichotomy lends it a fascination missing in Blier’s previous (IF I WERE A SPY) and subsequent films (which include the inexplicably overrated GET OUT YOUR HANDKERCHIEFS and BEAU PERE).

There’s no such ambiguity in this novel. It aims to shake up middle-class readers mightily with its account of two longhaired louts on an aimless crime-spree through France. The narrator is Jean-Claude, the more assertive of the pair, who despite his criminal ways is deathly terrified of prison; the other is Pierrot, who early on, during a botched carjacking, gets shot in the thigh. He’s scared he’ll never be able to get an erection again, leading Jean-Claude, ensconced in a house that isn’t theirs, to sodomize his pal (a bit that didn’t make it into the film). They also meet Marie-Ange, a hot-to-trot hairdresser who becomes the guys’ intermittent travelling companion and fuck-mate, although she can’t seem to orgasm.

The freewheeling tone shifts rather heavily when Jean-Claude and Pierrot decide to sharpen their criminal skills by cutting their hair (to better fit in with straight society) and hanging around a jail in the hope that a hardened parolee will show them the ropes. They wind up glomming onto Jeanne, an elderly jailbird, in a sojourn that’s unexpectedly poignant (for more so than in the film). It ends horrifically, though, with Jeanne, who mourns the loss of her period, hitting upon a macabre way to get it back.

From there the bad behavior starts back up, with Jean-Claude and Pierrot reconnecting with Marie-Ange, who manages to finally get in touch with her inner nympho. Thus our “heroes” resume their life of thievery and promiscuity, topped off with an unexpected murder, the (willing) kidnapping and deflowering of a sixteen year old girl, and a final line that’s nearly as evocative as the opening one.

All this is put down in a convincingly rendered counterculture brogue, littered with period specific slang, that was brilliantly translated into English by Patsy Southgate. Not everyone will respond to this shock-fest, but it has value to the modern reader. Especially worthy is its portrayal of a type of historical personage we tend to think of as peace and love-minded but whose true motives, as revealed here, were far darker, more self-centered and violent.

See also: