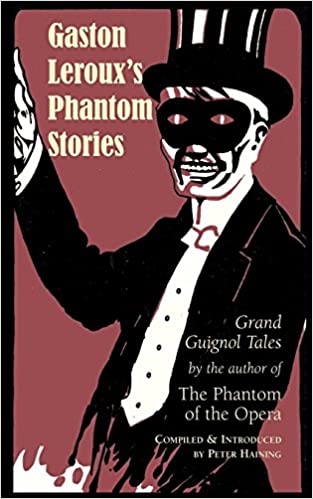

Edited By PETER HAINING (Apocryphile Press; 1980/2006)

Edited By PETER HAINING (Apocryphile Press; 1980/2006)

France’s Gaston Leroux (1868-1927) is destined to be known as the author of the immortal PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1911), which explains the title of this collection. In truth, however, only one of the nine Leroux stories collected here is PHANTOM related: “The Real Opera Ghost,” a nonfiction account of the actual crimes that inspired the novel.

As for the rest of these “Phantom Stories,” they span the years 1908 to the author’s death. Many appeared in the pages of Weird Tales alongside the likes of H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith, yet showcase an altogether unique and idiosyncratic gift for grand guignol horror that still manages to startle. Kudos to Peter Haining, who compiled this collection and provides a learned introduction detailing Gaston Leroux’s life and career.

The aptly named “A Terrible Tale” starts things off. It’s the strongest of the stories and also the most outrageous, involving a severely crippled mariner, his similarly maimed ex-shipmates and a gruesome cannibal banquet. Nearly as potent is “The Woman with the Velvet Collar,” about a strange woman who, it’s rumored, was guillotined yet still lives, with a velvet collar being all that holds her head in place.

“The Mystery of the Four Husbands” showcases Leroux’s talent for the whodunit (a form he all-but invented in 1907’s THE MYSTERY OF THE YELLOW ROOM) in its consistently unpredictable account of a woman who marries several men, all of whom meet violent deaths. “The Inn of Terror” relates how a naive young couple encounter unspeakable horror at the titular inn, where several people were previously murdered. As for “The Crime on Christmas Night,” it’s a deceptively quiet tale of Christmastime murder that steadily accumulates in gruesome momentum; like many of its fellows, it’s related in the form of a story within a story, which in this case proves a clever ruse in moving the narrative along, with the teller of the tale constantly goosed by his companions to get to the good parts.

There’s also “In Letters of Fire,” which with its satanic pact based narrative is the book’s only supernatural account. “The Gold Axe” relates in singularly perverse fashion how a decrepit old woman came to her present lowly stage, while “The Waxwork Museum” conclusively demonstrates that it’s never a good idea to try to face up to one’s fears at night, especially in a wax museum.