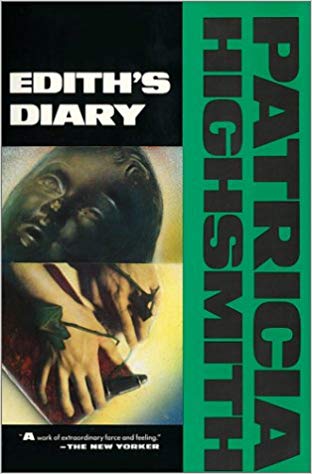

By PATRICIA HIGHSMITH (The Atlantic Monthly Press; 1977/89)

By PATRICIA HIGHSMITH (The Atlantic Monthly Press; 1977/89)

See ALSO: DEEP WATER

A late period novel by the great Patricia Highsmith that showcases its author’s past-her-prime pedigree all too well. It sees Highsmith, who prior to EDITH’S DIARY published the majority of her novels in the mystery-suspense market, assuming a slightly more mainstream-friendly mode (a gambit that appears to have paid off in the enthusiastic blurbs by The New Yorker and other high profile sources). In the Highsmith cannon this is ranks as a lesser entry, yet even medium-strength Highsmith is preferable to most other writers’ successes.

The ostensible subject is Edith, a young married woman, and her diary. Highsmith’s true concern, however, was the turbulence of America in the years 1955-75, as expressed through its protagonist’s harried existence.

The novel begins with Edith, an aspiring writer, purchasing a diary. As her life grows increasingly fraught over the ensuing twenty years, with her husband Brett leaving and placing his invalid uncle George and loser son Cliffie in her care, Edith makes fake entries in her diary about how well things are going. She even provides Cliffie with an imaginary wife and child to go with the glamorous engineering job she writes about him having (in reality he works part time at a restaurant and has no significant other to speak of, much less an offspring). But of course with all this fantasizing Edith’s sense of reality grows increasingly skewed, to the point that Brett and others begin to worry about her sanity.

If that were all there was to this novel it might be stronger than it is. In fact, the above plot summary is but a portion of a narrative that pivots on a politically minded periodical Edith runs, through which she covers the decade’s many upheavals from a left of center perspective (and so parrots Highsmith’s own views). Cliffie’s various issues provide another major plot strand, with Cliffie coming to increasingly dominate the book in his doomed affection for a flighty young woman who consents to a single date and then dumps him, thus making him into, essentially, another of the lovesick male protagonists who tended to headline Highsmith’s novels.

Another Highsmith mainstay occurs in the form of a murder (of sorts) that occurs in Edith’s house, and in the way the protagonists react to it (or don’t). What’s very un-Highsmith-like is the sloppiness of the writing. A large part of the charm of her books was the casual, unselfconscious prose, but here that tendency is taken to uncomfortable extremes, with parenthetical asides used to lazily fill in important plot points and a lot of superfluous detail.

The trade-off, as in Highsmith’s other late-period publications (such as PEOPLE WHO KNOCK ON THE DOOR and FOUND IN THE STREET, both of which, like EDITH’S DIARY, have their share of strengths and flaws), is the atmosphere of staunch realism that is maintained throughout. As bleak and at times bizarre as the narrative becomes, it’s never less than fully convincing in its details.