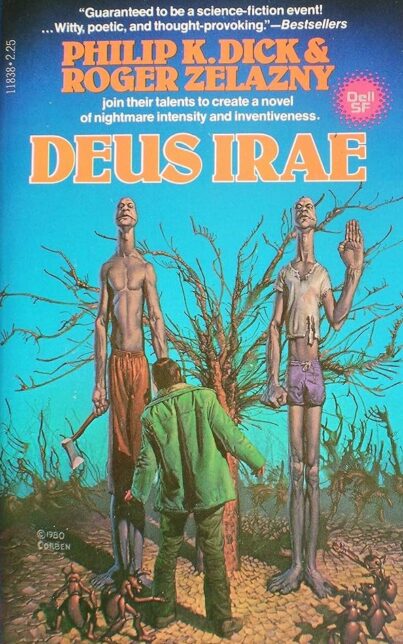

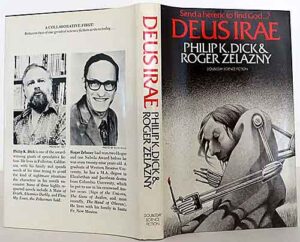

By PHILIP K. DICK, ROGER ZELAZNY (Dell; 1976/80)

In science fiction terms this book marked a true dream collaboration, it being the first and only novel by Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny, two of the genre’s most gifted late twentieth century practitioners. In reality, though, DEUS IRAE was an abandoned Dick project that was completed by Zelazny, and like most such novels it’s a severely mixed bag, showcasing the maniacal invention of Dick and the intellectual heft of Zelazny without ever uniting the two.

The former’s fascination with faith and divinity is evident, as is the latter’s penchant for apocalyptic fantasy in a story set in a post-nuclear America (a subject Dick had previously explored, quite ably, in DR. BLOODMONEY). The Servants of Wrath, a government-instituted strand of Christianity, has taken hold amid the surviving populace. Tibor McMasters is a painter in the employ of one Father Handy, who sends Tibor on a “Pilg” (pilgrimage) to locate the God of Wrath, who apparently takes the form of a fellow named Carl Lufteufel (the creator of the nuclear device that led to the Earth’s current state), and take a photo of his face so it can be painted into a church mural. This is despite the fact that Tibor lacks arms and legs, relying for mobility on a sophisticated electronic contraption that never seems to work right.

The Pilg begins in Charlottesville, UT and stretches to Los Angeles, CA, and involves a massive supercomputer known as “the Great C” that functions as, essentially, a pre-Siri/Alexa, as well as talking bugs, lizard people and mutant beings known as runners. There’s also Pete Sands, a young fellow obsessed with drug-induced visions (including a levitating clay pot through which the voice of God emits) who wants to prevent Tibor from finding Lufteufel, and Jack Schuld, a bounty hunter contracted by a secret police organization to kill the God of Wrath.

Included are many learned dissertations on theology and the First Century AD, a period Dick, in light of the “religious experience” he underwent in 1974 (dramatized in VALIS), believed never actually ended. Drugs also play an important part in DEUS IRAE, just as they did in Dick’s life. That sense of gonzo engagement, alas, is undercut by Zelazny’s more studious approach, which incorporates Da Vinci, Zen Buddhism and a severely underdeveloped “cretin girl” named Alice, resulting in an enticingly bizarre concoction that’s never especially readable or satisfying.

That malaise extends to the final pages, which involve yet another last minute character addition, and appear to have been leading up to an ironic coda that never quite arrives, suggesting that Dick was right to leave the novel incomplete. If he of all people couldn’t come with a suitable conclusion then perhaps there simply is no real ending, and if there was one Zelazny was unable to find it.