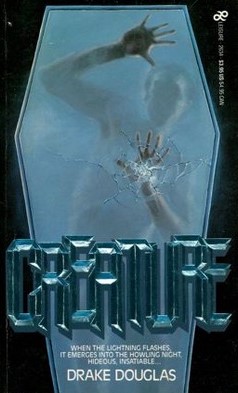

By DRAKE DOUGLAS (Leisure; 1985)

By DRAKE DOUGLAS (Leisure; 1985)

An example of something that’s all too common in horror fiction: a paperback novel whose contents diverge quite radically from the packaging. That packaging portends a trashy horror fest a la Stephen King at his most lurid, and indeed the first half of the book delivers just that, with a naive English traveler finding himself stuck in a rural Austrian village. Eventually he enters a foreboding castle and discovers…something.

Cut to England, where the traveler’s brother decides to go in search of his missing sibling. He manages to track him down in another remote Austrian castle, around which several locals have been found dead with their hearts missing from their chests. It seems the first brother is harboring an inhuman creature, and that critter is (no joke) Frankenstein’s Monster. The latter is looking to resurrect his bride—who, as you’ll remember from the original novel, was destroyed by Dr. Frankenstein—by stealing peoples’ hearts. Thus the two brothers find themselves inextricably drawn into an undead marital drama that, as you might guess, ends badly for everyone.

CREATURE is neither a parody nor an homage, but rather a sincere attempt at continuing Mary Shelley’s immortal story. As such it comes complete with some lengthy Man-Should-Not-Tamper-With-What-He-Does-Not-Understand ruminations, and a despairing tone that fits right in with Ms. Shelley’s worldview. The only problem here is that author Drake Douglas (of the popular nonfiction tome HORRORS!) can’t seem to distinguish between the FRANKENSTEIN novel and the 1931 movie version, which are of course completely different entities yet are interchangeably referenced.

Beyond that this CREATURE is determinedly old-school in its approach. The pacing is quite deliberate, there’s nary a cuss word to be found, and the nasty business is kept discreetly off-stage. Surprisingly enough, it’s an extremely readable account, with a propulsive narrative drive that somewhat offsets the dourness, and prose that positively drips with foreboding atmosphere. That’s not to say Douglas’s approach is without flaws: the characterizations are overly perfunctory (the sibling protagonists are among the dullest I’ve ever encountered), the story is often agonizingly uneventful and, at 398 pages, the whole thing is far too long.