By BARRY HAMMOND (Fathom Press; 1982/2025)

By BARRY HAMMOND (Fathom Press; 1982/2025)

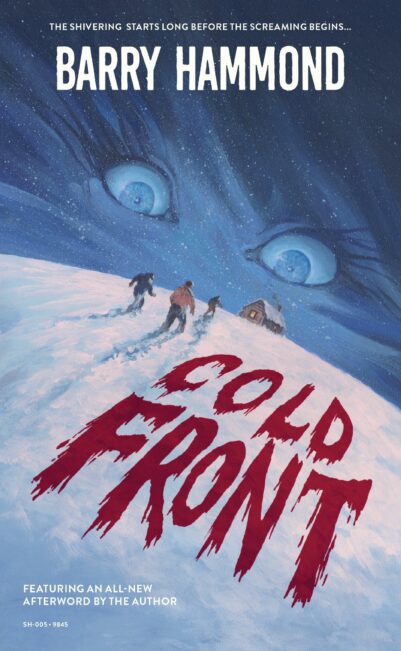

One of the rarest horror novels of the eighties. Until 2025, in fact, Barry Hammond’s COLD FRONT, initially published in 1982 by New American Library’s Canadian arm, was all-but impossible to find. Now it’s been reprinted by Fathom Press, complete with a newly written afterword by the author, who claims he wanted to make a film but “realized a pen and pad, typewriter and paper were a lot less expensive” than a movie, and was attracted to “the idea of a legend/monster that was Canadian”—which is to say a Wendigo, or “beast that walks on the wind.”

COLD FRONT is, first and foremost, thoroughly Canadian, as is made explicit by one of its characters, who sarcastically muses that “It was your typical Canadian story…(akin to) the boring plays they were always awarding prizes and grants to and putting on CBC.” The protagonists are a trio of scumbags: the Indian Jimmy, the Ukrainian John and the French Ken, who work at a remote Canadian hotel. The book begins with this mismatched threesome robbing and killing their employer Arv and then hitting the road, just as a huge snowstorm commences.

Ken’s crappy used car quickly strands him and his accomplices. Weirdness becomes apparent when Arv’s corpse goes missing from the back seat, and is later found “stretched and ripped apart, hanging in the trees.” Nearby is a cabin to which the men make their way. The place contains a single resident, an unearthly young woman who evokes a powerful erotic charge in Jimmy, John and Ken.

There’s not much to COLD FRONT narratively, with the protagonists existing to be picked off by an unseen Wendigo lurking in the woods, which of course has some connection with the young woman. The book, however, excels in grit and physical detail. Hammond’s descriptions are strong and convincing, offering a minute-by-minute accounting of the protagonists’ travails through a microscopically rendered snowscape. The fact that Barry Hammond is not a horror writer by trade is another point in the book’s favor, as its refined prose and unpredictable rhythms are unique and compelling.

The final pages take things in an altogether different direction. It’s here that the young woman’s eroticism is finally acted upon and the proceedings come to increasingly feel like an example of Japanese ero-guro (or erotic grotesque) art, in passages involving masses of corpses “black and purple with decay…their throats would stretch open to suck a foul wind through the dead air passages before disgorging a heavy, coagulated black blood” and semen that “shone in greyish-white trails on her skin, sliding as she moved, unable to adhere firmly to her glistening flesh.” Its story may be familiar splatter movie fodder, but this book is definitely one of a kind.