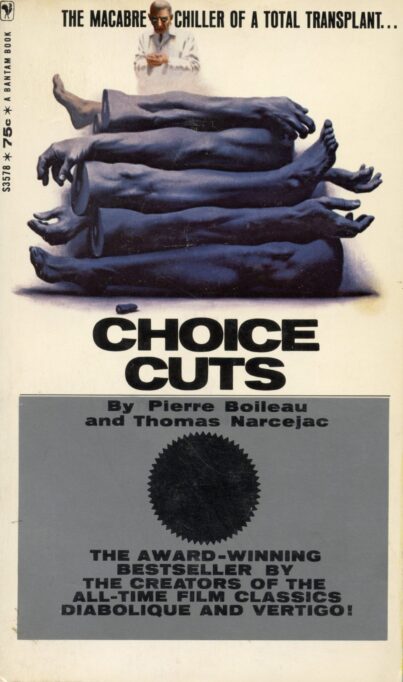

By PIERRE BOILEAU, THOMAS NARCEJAC (Bantam; 1965/66/68)

By PIERRE BOILEAU, THOMAS NARCEJAC (Bantam; 1965/66/68)

Those who claim there’s “no such thing” as dated media need to read this France-originated mystery. Initially published back in 1965, and translated into English the following year, CHOICE CUTS (ET MON TOU EST UN HOMME) is, despite some affecting passages, strictly a product of its time.

It certainly had a pair of talented authors: Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, of SHE WHO WAS NO MORE (a.k.a. DIABOLIQUE) and THE LIVING AND THE DEAD (a.k.a. VERTIGO) fame. CHOICE CUTS, about a total body transplant, evidently seemed quite novel and disturbing in the 1960s (judging by critical blurbs like “As nasty a piece of fiction as ever came out of France” and “One of the most macabre yet blackly funny horror mysteries ever written”), but that conception is no longer unique or, as detailed in these pages, plausible.

The “choice cuts” originate from Rene Myrtil, a condemned murderer who apparently experienced a change of heart in prison, and wants his soon-to-be-executed body to go to medical research. The conscious-less Dr. Anton Marek, who’s figured out how to graft limbs onto bodies without any complications, agrees to the wishes of Myrtil, and following his execution sews portions of his anatomy onto the bodies of seven seriously injured individuals.

The narrator, a government functionary, is tasked with overseeing the experiment, and tracking the fortunes of “The Resurrected Club.” He notes some unsettling side effects, such as the fact that an artist who’s been given one of Myrtil’s hands finds himself painting uncharacteristically abstract canvases, while a school teacher who’s received the murderer’s pelvis (that wording is about as sexually descriptive as this book gets) gains a prodigious appetite that doesn’t stop with food, and a banker with Myrtil’s head finds himself undergoing dramatic personality changes (to gauge just how dated this book is, note a supposedly outrageous plot point that involves a priest finding a—gasp!—tattoo on his newly grafted arm).

Inevitably the club members grow disillusioned and depressed, and begin committing suicide. But are all these deaths truly self-deletions? And why does the fellow who received Myrtil’s head seem so calculating?

Predicting the twist ending is far from difficult, although I did have trouble figuring out how it is that the protagonist takes until the end of the book to (SPOILER ALERT!) realize that transplanting the head of a brilliant murderer onto another man’s neck might not be a good idea. As I’ve come to expect from Boileau and Narcejac, the novel is well written (and well translated by Brian Rawson), but its time has come and long since gone.