By WALTER DEAN MYERS (Dell; 1977)

By WALTER DEAN MYERS (Dell; 1977)

Not to be confused with the 1983 movie of the same name, this BRAINSTORM is a YA science fiction novel that clocks in at 90 pages. Like many a young adult book it has a number of agreeable elements, but is done in by a simplistic, paint-by-numbers treatment.

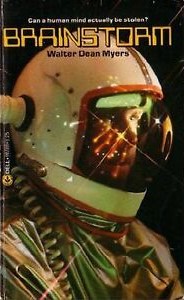

The novel is notable, firstly, for the fact that it contains numerous full page photographic illustrations by Chuck Freedman. Depicted is a very old school conception of space travel, with the ladies all wearing miniskirts and headbands, and the guys dressed in STAR TREK-like uniforms with prominent shoulder pads. We also get several close-ups of people screaming and, most striking of all, wide shots of the protagonists silhouetted against vast extraterrestrial vistas. It’s just too bad the printing quality is so poor, rending what look like pretty cool pictures in a grainy and indistinct manner.

The text is rendered in standard kid novel prose, with short declarative sentences designed to be as simple and easily understandable as possible (“Greg started to run. He didn’t get far. He dropped to his knees crying”). The story is somewhat intriguing, involving several people emerging from a summer storm with their minds wiped. More storms bearing the same results follow, leading FORTIA, the “army of the world,” to the conclusion that the storms are the result of a “powerful ray” emitted from the planet Suffes.

An expedition to the planet is organized, with a crew of teenagers selected to man a spaceship through a time warp (the particulars of which are left unexplained) that will only take three days but cause them to age fifteen years. Upon setting down on Suffes our now-thirtyish crew learns that the Suffesians look human but for their “large and lifeless” eyes, and that the mind-wiping rays are in effect on Suffes just as they are on Earth. It seems the Suffesians are stealing humans’ brains in order to view their contents in the form of a TV broadcasts, as their own minds have atrophied to the point that they lack the means to create their own diversions.

Pretty interesting, no? The kid-skewering prose lessens the book’s impact considerably, but the ideas contained here are worth exploring further. So too the illustrative photos, which could have produced worthwhile results if only the print quality weren’t so lousy.