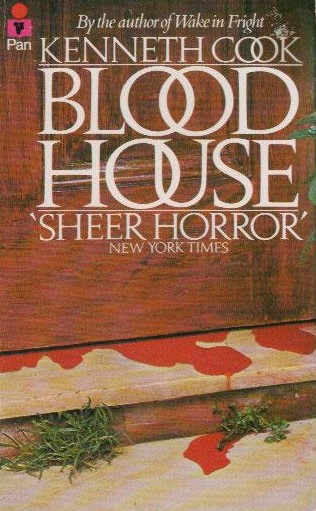

With this outrageous novel Australia’s late Kenneth Cook turned out his finest work since WAKE IN FRIGHT. That 1961 novel, for those who don’t know, contained an unforgettably rancid portrayal of Australian lowlife that remains unsurpassed—well, almost unsurpassed, as the short and sharp BLOODHOUSE imparts an even grungier fictional portrait of the land down under. It’s been rumored that tourism into Australia declined precipitously after WAKE IN FRIGHT’S publication, and I’m certain BLOODHOUSE, about a wild night at a sleazy hotel located on the outskirts of Sydney, will probably never be endorsed by the Australian tourist board.

What occurs in the “bloodhouse” over the course of the evening in question is interspaced with a succeeding court inquest, in which it’s established that amid “a scene of squalor, terror and confusion”—indeed, a “glimpse of Hell”—someone was murdered. We don’t immediately find out the identity of the victim, but the knowledge of an impending death hangs over the remainder of the book, which builds to a near-unbearable pitch of suspense as the hotel’s inhabitants grow increasingly rowdy.

Rape, prostitution, mass brutality, underage drinking, a fatal car accident and a lost cat all contribute to the murder in question. The characters, each of whom ends up thoroughly dehumanized, include the skuzzy slaughterhouse workers Verdon and Harris, as well as Peter, an effeminate young man looking to get laid, a naïve young woman who falls prey to the lusts of all three, the hotel’s obese proprietor Mick and his equally rotund wife Jenny.

Amid the drunken chaos, all of it described with unerring clarity and control, Cook manages to insert his trademarked naturalistic observations (such as a description of a cat food can whose label guarantees it not to be kangaroo meat) with admirable unobtrusiveness. Yet Cook also tries something new, imbuing his standard brand of gritty drama with a strain of gruesome, pitch-black comedy. It’s an approach that foreshadowed the later novels of Charles Willeford, as well as the films of the Coen Brothers and Quentin Tarantino, but was quite unprecedented in 1974. Cook also provides a final twist, involving the particulars of the foreshadowed murder, that I guarantee you will not be able to predict.