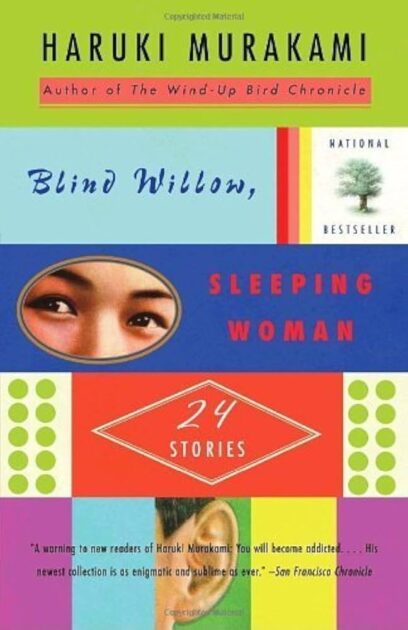

By HARUKI MURAKAMI (Vintage International; 2006/07)

By HARUKI MURAKAMI (Vintage International; 2006/07)

I’ll confess I’m not as fanatic about the work of Japan’s Haruki Murakami as many mainstream critics—note this book’s blurb page, filled with adjectives like “masterly,” “virtuosic,” “extraordinary” and so forth. I do, however, appreciate Murakami’s gift for the odd and oft-kilter. That gift is in abundant evidence in the 24 stories collected in BLIND WILLOW, SLEEPING WOMAN, which also showcases Murakami’s unfortunate penchants for overwriting and self indulgence.

The stories are filled with mysteries and conundrums that in true Murakami fashion are rarely if ever explained. An exception to that occurs in the final story “A Shingawa Monkey,” about a woman who can’t remember her name; the reason, you can be sure, is thoroughly bizarre, and involves the titular monkey. Murakami also tends to focus on odd and evocative imagery at the expense of narrative cohesion, as in a boy’s description of a dream knife stuck in his head “like the bone of some prehistoric animal on the beach” that concludes the story “Hunting Knife.” In all cases normality, as a state of being or even a concept, is left far behind.

Not all the stories work. In the ho-hum “Dabchick” job applicants in an enigmatic company have to figure out the password Dabchick—a type of water-bird, we learn in the joke ending, which runs the company. Beyond that I found the book’s least interesting stories, ironically enough, to be the most overtly horrific ones, such as “The Mirror,” about a man who sees a demonic version of himself when he looks in a mirror, and “The Seventh Man,” in which a distraught man describes seeing his friend “K” (a Kafka reference?) disappearing into a giant wave and beckoning at him to come along—luckily for the narrator he chooses to remain in the here-and-now. Also in this category is “Crabs,” in which we learn it’s not a good idea to eat bad crab meat.

I was more enamored with “Man Eating Cats,” an altogether odd account of a Japanese couple residing in Greece, some deadly man eating felines and a literal vanishing (into thin air). “Airplane: Or, How he Talked to Himself as if Reciting Poetry” tells of man who talks to himself, as the title makes clear, in poetic utterances that he later forgets; don’t expect any explanation, but the tale has a pleasantly oft-kilter ring to it. “A Poor Aunt Story” finds a man getting a “poor aunt” stuck to his back, a predicament related in a disconcertingly offhand, matter-of-fact manner. “The Ice Man,” which in his introduction Murakami claims was inspired by a dream his wife experienced, is the cockeyed tale of a woman who marries, and is impregnated by, a literal ice man.

The standout tale in my view is one of the few that has no fantasy component at all: “Tony Takitani,” an alternately sad and funny account of a lonely boy with an odd name who grows into an equally lonely man who marries a woman with a massive shopping addiction. The results are as fluid, unpredictable and ultimately unforgiving as life itself.