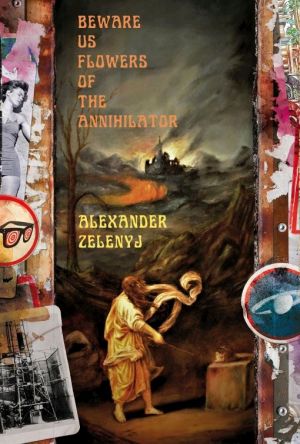

By ALEXANDER ZELENYJ (Eibonvale; 2024)

About BEWARE US FLOWERS OF THE ANNIHILATOR, the latest and most comprehensive collection of stories—26, to be exact, contained in a near 500-page whole—by Canada’s master of elegantly drafted bizarrie Alexander Zelenyj (THESE LONG TEETH OF THE NIGHT), five things are apparent:

1). Mr. Zelenyj has an unmatched gift for evocative titles

If this book’s moniker isn’t evidence enough, there’s also “Rat-Eaters in Lucifer’s Land,” certainly a grabber of a title, and the story has an opening line to match: “He dreamed the same dream that had plagued his sleep for what seemed like forever: the dream of the Eating Things.” Other great titles include “Houses Within Houses Within Houses Within,” about an extraterrestrial “orb-thing” drawn to a uniquely designed house, and “People-Eater and The Wolf Inside,” a designation that’s quite literal, as one of its two protagonists is indeed a people eater (as in cannibal), while the other conceals highly anti-social (as in wolf-like) proclivities.

2). Zelenyj’s conceptions are every bit the equal of his titles

Take “Love-Goggles 1966,” about a pair of spectacles that make everyone the wearer sees resemble Mila Kunis, or “Young, But Tomorrow,” which begins with a troubled man voicing the major issue facing him—“There’s a giant skull floating outside my apartment window”—and builds from there. There’s also “We Are Alone,” about a “lightweb” that allows people to fly, and eventually sees “mankind ascend like angles into the heavens,” but also leads to a most disquieting revelation about our place in the universe.

3). Zelenyj is a rare example of a Canadian author who isn’t afraid to flaunt his nationality

That’s evident in the book’s lead story “Peacekeeper and The War-Mouth,” which deals bluntly with anti-immigrant sentiment in Canada in the form of a bullied Czech boy with a most peculiar deformity, and also “The Electric Voice of Summer,” set at a Port Elgin, Ontario based summer camp attended by a girl who believes she’s (literally) haunted; the story contains pointed references to Canadian communities like Windsor and Goderich, and a mention of the “Great Brushfire of 1950,” a.k.a. the British Columbia based Chinchaga Firestorm that occurred in June-October of 1950.

4). In contrast to all the pretend surrealists currently at work, Zelenyj understands dream logic in and out

For corroboration see “A Savage Path,” a powerful dose of reality displacement involving a “God-Egg,” random murder and suicide, and “Little Boys,” in which an instance of time displacement is heralded by a prehistoric flower sprouting from the control panel of an airplane. “The Threat from Earth,” meanwhile, offers a Bradbury-esque account of two boys on a bird hunt that somehow doubles as an oblique account of alien invasion.

5). The man simply knows how to spin a great yarn

That’s evident in “Oppenheimer’s Door,” about life after the “Great Emptiness,” which has a definite connection with the doings of a certain Mr. Oppenheimer—not an especially novel concept, but what the story’s protagonist opts to do with his time in the Emptiness is quite unexpected: he digs up the coffin of his widow so he can spend his final hours with his long-dead beloved. “Sister-Biter” abandons the quasi-humorous tone of so many of these stories, but fully retains the strangeness (with a character who speaks of tasting the sun) in its unsettling depiction of a disturbed boy who among other things likes to bite his little sister. Then there’s “The Punished World,” which takes the form of a poem yet satisfies as a prose narrative relating a DROWNED WORLD-esque science fiction reverie.

Science fiction, surrealism, Canadiana and great storytelling: not too many books these days can be said to Have It All, but BEWARE US FLOWERS OF THE ANNIHILATOR can and does.