By GASTON LEROUX (Elektron Ebooks; 1911/2013)

France’s Gaston Leroux is of course known for THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, but his full output was far more varied. Novels like THE DOUBLE LIFE, about a man possessed by the reincarnated spirit of Cartouche, and THE MACHINE TO KILL, in which the brain of a murderer is implanted into a robot man’s body, evinced a definite talent for black-humored outrage, and BALAOO is very much in the same arena, being the altogether outrageous account of a pithecanthrope, or ape-man.

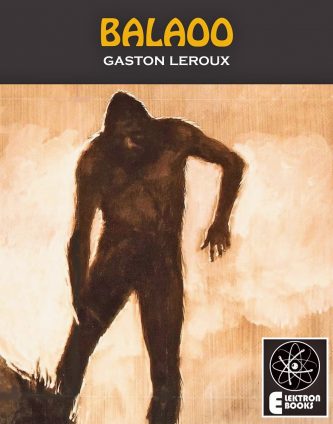

Created by a mad scientist, Balaoo can pass for human but retains his animal nature. He lives in an ornate tree-house, and is pressed into committing crimes by a band of forest-dwelling criminals, resulting in an accidental murder that alerts the authorities to Balaoo’s existence. But this pithecanthrope has a soft side, as evinced by his longing for Madeleine, the angelic daughter of the scientist who created Balaoo.

If any of this sounds familiar, that’s because the story is essentially a rehash of the aforementioned PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, with a forest in place of an opera house. Yet it also foreshadows a certain 1930s-era film involving a dangerous yet pure-hearted ape in love with a human woman, especially in the climax, which involves a pursuit across the rooftops of Paris and a fall from a tall building. Yes, BALAOO had a sizeable impact on early 20th Century pop culture, and was adapted to film several times (including 1913’s film version of BALAOO (below), 1927’s THE WIZARD and 1942’s DR. RENAULT’S SECRET). That, however, doesn’t change the fact that the novel is far from Leroux’s best work.

BALAOO (Clip with French Subtitles)

Quite simply, it’s wildly disjointed and uneven, with a narrative that continually slips out of the author’s control. The criminal band to whom Balaoo is in thrall, for instance, play a huge part in the book’s opening half yet inexplicably sit out much of the latter, while Madeleine’s dull bourgeoisie suitor Patrice, who exists solely as a foil to Balaoo, is given far too much face-time. The racial implications of Balaoo’s existence are another problem, elucidated in a manner that appears uniformed at best, and outright racist at worst (and the primary reason, I’m guessing, that the novel is currently so little known).

Where BALAOO excels is in Leroux’s oft-spectacular set-pieces, in which his penchant for the outrageous is given full reign. These include an unforgettable mid-book showdown between Balaoo and some overzealous lawmen that’s enlivened by the pithecanthrope’s ability to communicate with forest animals, who do his bidding in a brutal succession of captures and killings, and an even wilder interlude in which Balaoo trains a fellow simian to impersonate human behavior.

Unfortunately, the climactic rooftop chase is related for some unfathomable reason through a succession of mock newspaper clippings, which dilutes the suspense considerably and closes the novel out on an unexciting note. So no, BALAOO is hardly a masterpiece, but it definitely has its pleasures.