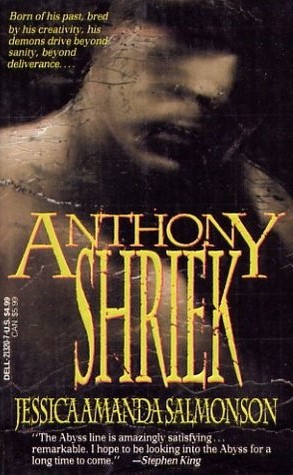

By JESSICA AMANDA SALOMONSON (Dell; 1992)

By JESSICA AMANDA SALOMONSON (Dell; 1992)

Anyone wondering why Dell’s fabled Abyss horror line, which promised “Horror unlike anything you’ve ever read before,” didn’t last beyond the early nineties need only read this, one of Abyss’ signature entries. ANTHONY SHRIEK isn’t a bad novel, mind you, just a severely bloated and self-indulgent one (problems that afflicted quite a few Abyss titles).

In this respect it’s not unlike the title character, a painfully neurotic, self-absorbed college student based in Seattle. Not that Anthony doesn’t have good reason to be neurotic and self-absorbed: his childhood, we learn, was quite horrific, and he’s possessed of unwanted supernatural abilities that have something to do with the odd vortexes he obsessively paints.

Jessica Amanda Salomonson, whose first horror novel this was, lavishes an awful lot of verbiage on Anthony’s day-to-day activities, and also those of his girlfriend Emily, a freaky sort who fancies Anthony’s “demonic nature,” and Candice, a young woman with whom Anthony and Emily have a threesome (of sorts). Salomonson also includes lengthy descriptions of Anthony and Emily’s Seattle haunts (one thing nobody can say about this novel is that it lacks a sense of place), along with plenty of mythological allusions, philosophical chatter and self-written poetry, including an entire chapter consisting of back-to-back poems with titles like “Because the Night” and “Blood and Roses.”

There’s also a plot in there somewhere, involving Anthony’s faltering attempts at making dues with his tortured past via an otherworldly realm called Nightland, which is accessible through his vortex paintings. But it seems Nightland is haunted by malevolent demons from Anthony’s past that have not just him but also Emily and Candice in their sights.

For a novel so consumed with poetic apprehension the hallucinatory passages of ANTHONY SHRIEK are a disappointment, being too literal in their conception, and so lacking the confounding frisson of true surrealism. In the novel’s defense, it is curiously readable despite all the bloat, suggesting that shorn of a hundred or so pages it might well have been great.