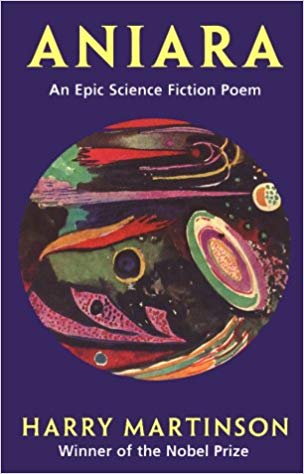

By HARRY MARTINSON (Story Line Press; 1956/98)

By HARRY MARTINSON (Story Line Press; 1956/98)

The one and only science fiction epic poem, originally published in Swedish and reissued here in its second English translation by Stephen Klass and Leif Sjöberg (the first was by Hugh MacDiarmid and Elspeth Harley Schubert). It’s said to have been instrumental in winning its author Harry Martinson (1904-78) the 1974 Nobel Prize (nothing else Martinson wrote had a fraction of the impact of ANIARA, something that, as the biographical notes included here make clear, upset him greatly), and remains an undeniably impressive example of visionary space opera.

Comprised of 103 linked poems broken into short rhythmic stanzas that at times rhyme, it is admittedly not an easy read. Brilliant it is, but dense, protracted and underplotted are also words that adequately describe ANIARA, with a perusal of the introductory plot summary required for a full understanding of a narrative that isn’t fully fleshed out in the text.

The translators helpfully provide an explanation for the poem’s odd mixture of casual reportage (“A man from High Command stands amid the people/in the great assembly-halls abaft./He pleads with them not to despair, but view their fate/in the clear light of science”) and formal verse (“the photophage, with unimaginable ire/suddenly breaks down and flings the fire/of an exhausted love’s concluding blaze/into the photophage’s thankless rays”), something I’d opine was due to the translation but was apparently inherent in Martinson’s initial Swedish language inception. A glossary is also included, which fills us in on the many esoteric words and phrases—such as “goldoneva” (Sanskrit for divinity) and “kieselguhr” (a “friable chalky earth used to absorb the nitroglycerin during the manufacture of dynamite”)—that fill the text.

Yet conceptually ANIARA is quite robust. It takes place on a vast spaceship where thousands of people reside. These folk are fleeing a radiation-suffused Earth en route to Mars, but the ship is knocked off course and, despite false reassurances by its privileged overlords, is destined to remain that way. The narrator, a sensitive sort suffused with nostalgia for the planet he left, is charged with operating the Mima, a sort of virtual reality theater to which the ship’s multitude flock. But the Mima is developing a mind of its own that the narrator is unable to penetrate or diagnose, and eventually shuts itself down entirely. This greatly riles up the ship’s passengers, and as the years drag on they give way to mass despair, and the formation of suicide cults, hedonistic dance crazes and the sentencing of the protagonist to death.

Obviously any number of metaphors can be read into this account, although its depiction of space travel was apparently based on a deep seated fascination held by Martinson, who according to a first-hand quote (included in the introduction) experienced “the illusion of being located on a space ship. At first this feeling was chaotic and full of anxiety, but gradually the visions began to clarify themselves inside him…” The detail of the author’s descriptions of life aboard the Aniara, whose inhabitants are careful to observe the demarcation of morning, noon and night despite the fact that those things don’t exist in space, are worthy of a more conventionally drafted science fiction epic.

That last point brings up the question of whether ANIARA’s poetic overlay is absolutely necessary, or merely a gimmick to bolster a conventional story. To be sure, the idea of people attempting to subside aboard a massive spaceship isn’t particularly novel, and there’s not much in the way of plot twists to be found here. But Harry Martinson’s underlying concerns are more emotional and expressionistic, with longing and isolation being the book’s driving agents. Poetry, then, is an entirely appropriate format.