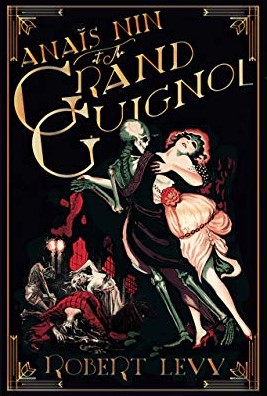

By ROBERT LEVY (Lethe Press; 2019)

Yet another example of mislabeled literary horror. The H word, you’ll find, was largely omitted from descriptions of ANAIS NIN AT THE GRAND GUIGNOL, which tend to consist of sentences like “a concentrated cocktail of Annaées folles splendor” and “a mysterious, whirling fantasy,” but make no mistake: this is very much a horror story from start to finish.

This isn’t to say that the novel is entirely without highbrow pretentions. It’s about the French-Cuban American writer Anaïs Nin (1903-1977), of whom a working knowledge is required for a full (or even partial) understanding of the contents. It deals with her years in 1930s Paris and her affair with Henry Miller, a period well covered in Nin’s published diaries (and the 1990 film HENRY & JUNE). This book purports to be a “lost” Anaïs Nin diary describing what happened after Miller’s wife June, with whom Nin was besotted, left her husband in 1934.

HENRY AND JUNE 1990 (Trailer)

As ANAÏS NIN AT THE GRAND GUIGNOL opens, Nin finds herself adrift. She’s still carrying on the affair with Henry Miller that broke up his marriage, but is troubled by memories of an incestuous relationship she had with her father (recounted in HOUSE OF INCEST) and her passion for June, who has decamped for New York City. She’s also finding that settling back into domestic life with her hubbie Hugo (whose presence was largely edited out of Anaïs Nin’s actual diaries but registers quite strongly here) is intolerably boring. One night, recalling a memorable outing she and June once shared, Nin decides to visit the infamous Theatre du Grand-Guignol, which specialized in gruesome horror dramas.

This visit changes her life irrevocably, with Nin finding herself oddly fascinated—and aroused—by the Guignol’s “sensual morbidity.” She becomes involved with one of the theater’s stock performers, a woman she comes to know as Maxa (as in “The Maddest Woman in the World”). Maxa, it transpires, is in thrall emotionally and sexually to a shadowy individual known as Monsieur Guillard, whose demonic charms quickly enrapture Anaïs.

Monsieur Guillard increasingly comes to dominate the book as Anaïs’s dark desires assume horrifically literal form and the elusive June makes a fateful reappearance. Judging by the ecstatic back cover blurbs all of this really wowed the literati, but horror readers, I suspect, won’t be quite as impressed. The book’s portrayal of dark desires erupting into the physical world is elegantly conveyed, but it’s not unprecedented by any means, and nor is its narrative arc (spoiler alert: the good guys win) all that exciting.

The novel deserves credit for its entirely convincing evocation of 1930-era Paris, and for replicating the florid voice of Anaïs Nin (in verbiage like “The animal sounds of our lovemaking echo in my ears, ring out across the bedroom and through the open door, and we fall into a dance of wordlessness, into the language of movement, the divine alchemy of the physical”). But as I stated upfront, this is very much a horror novel, and as such it’s so-so at best.