By MARTIN HAYES, R.H. STEWART (Markosia Enterprises; 2013)

By MARTIN HAYES, R.H. STEWART (Markosia Enterprises; 2013)

There exist many biographical resources on Aleister Crowley, the so-called “wickedest man in the world.” Here’s another, a graphic novel that attempts to encompass the entirety of Crowley’s life into a 108-page whole. That’s a pretty outlandish proposition, and one the book doesn’t succeed in doing justice (with 23 pages of notes included to properly fill things out), but it is an impressively researched and artfully crafted concoction.

Obviously the full breadth of Crowley’s existence can’t be encompassed, but as an evocation of Crowley’s universe WANDERING THE WASTE succeeds admirably.

Functioning as both a refutation of the sensationalistic claims that have surrounded Crowley’s life and a confirmation of his magical abilities (or at least his belief in them), WANDERING THE WASTE takes the form of a near-death reminiscence. The setting is the Netherwood guest house, circa 1947, where Crowley, suffering from heroin-induced bronchitis, spent his final days. He’s interviewed by an eager young writer named William Keyes, a fictitious character (and, the afterward assures us, “the only fictional character in the book”) to whom Crowley relates his life story.

We’re taken through Crowley’s unhappy childhood, dominated by ultra-religious parents obsessed with the imminent arrival of Christ on Earth. After his father’s death by cancer in 1887, Crowley embarked on a wave of bad behavior that included consorting with prostitutes and disemboweling a cat, and ultimately resolved to devote his life to magic. He joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, where he met Allan Bennett, a fellow he came to respect enormously.

It was Bennett who introduced Crowley to the illegal substances that would end his life, and become a fellow traveler in a journey involving esoteric rituals (presented here in exhaustive detail) and the formation of a new, occult-based religion. Other tidbits unveiled in these pages include the (unproven) fact that Crowley was a double agent for the British government, and that he allegedly inspired the V for Victory hand signal utilized by Winston Churchill.

Also covered is the anti-Crowley media blitz that occurred in the 1920s, inspired by the Crowley instituted Abbey of Thelema, a “quiet, almost monastic place to live and work…A place of sexual liberation, liberation from all of society’s imposed constraints.” The British media, obviously, had a different view.

The portrait conveyed by scripter Martin Hayes is of an ambiguous and complex individual who lived according to his own code (a dangerous proposition then and now). Obviously the full breadth of Crowley’s existence can’t be encompassed, but as an evocation of Crowley’s universe WANDERING THE WASTE succeeds admirably.

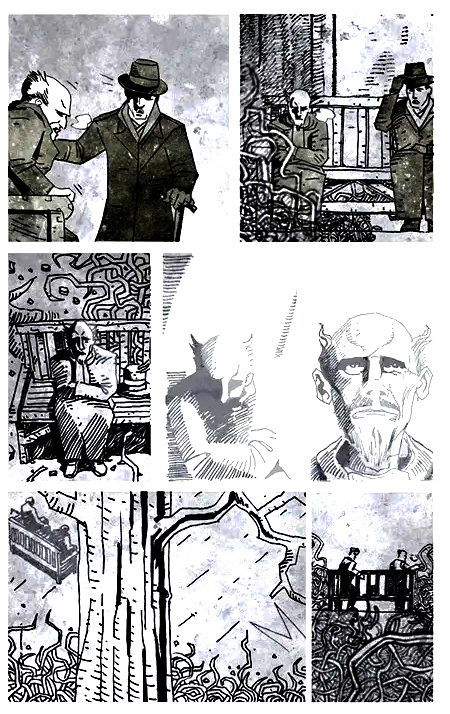

The artwork of R.H. Stewart must be singled out. Rendered in oft-sketchy black and white, Stewart’s drawings are concrete and abstract by turns, and often quite hallucinatory. This multi-pronged approach works in depicting its subject’s unconventional mindset, and also the book’s rush through several decades, which takes the form of an extended montage whose various moods are conveyed through the ever-changing, always impressive visuals.