By VLADIMIR BARTOL (Scala House Press; 2004)

Here’s a publication from the ‘00s that should have received far more attention than it did: the premiere English translation of Vladimir Bartol’s 1938 Slovenian language classic ALAMUT. A historical epic in the grand tradition, ALAMUT is notable for its subject, a fascinating one that has been surprisingly under-utilized in literature: the so-called “Old Man of the Mountain” Hasan-i Sabbah, a warlord who in the eleventh century created an order of formidable assassins by using sex and drugs to convince his youthful followers that they were in paradise—to which they fervently believed they’d return after carrying out Hasan’s orders.

Hasan became an unlikely counterculture icon in the late Twentieth Century (due largely to the novels of the late William S. Burroughs), while in the Twenty First he became notorious as the forerunner of Osama Bin Laden (who also utilized specially trained assassins whose actions were inspired by intimations of paradise). The primary inspiration for this novel, however, was apparently Benito Mussolini, many of whose beliefs and methodology are mirrored in ALAMUT, and to whom the first edition of the book was ironically dedicated.

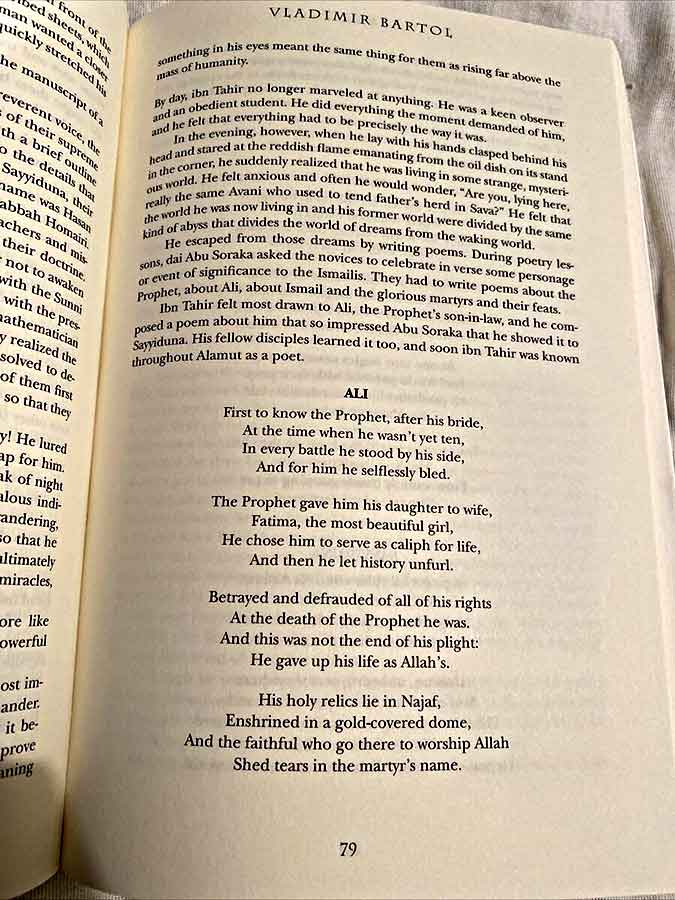

The tale begins with the young slave girl Halima being delivered to Alamut, a mountain fortress located in Northern Iran. There she joins several other slaves and Eunuchs who belong to Sayyiduna (“Our Master”) and reside in a vast garden located behind the castle. Also arriving in the area is Avani Ibn Tahir, who seeks to join Alamut’s fighting garrison in order to avenge the death of his grandfather, who was close with Sayyiduna, a.k.a. Hasan-i Sabbah. Other characters to which we’re introduced include Miriam, who’s romantically involved with Hasan; Suleiman, an especially dedicated cadet; Abu Ali, Hasan’s charismatic henchman; and Hassan himself, a brilliant, conflicted recluse given to lengthy philosophical proclamations and compulsive fits of anger.

It gradually becomes clear that Hasan is planning some vast experiment involving his soldiery and the slave gals. This leads to the book’s most arresting passage, in which three cadets, Ibn Tahir and Suleiman among them, are given specially grown hashish and taken into the garden, where they’re seduced by the slave girls and assured they’re in paradise. This transforms the dynamic of Alamut entirely, providing Hasan with the suicidal assassins he craves while turning the “hashashins” in question into minor celebrities among their fellows, while among the ladies a much darker dynamic becomes apparent involving jealousy and disillusionment.

On balance ALAMUT stacks up as a rather staggering feat of storytelling. Its author was a Slovene intellectual who turned out a meticulously researched and consistently absorbing narrative. True, there are some problems, mostly in the book’s final third; it’s there that Bartol ties up the many narrative strands he’s unspooled in oft-messy and unsatisfying fashion. One especially intriguing subplot, involving a young man who elects not to ingest the hashish Hasan has administered before being taken to paradise, is allowed to fizzle out entirely, while another, exploring the shifting relationship between Hasan and Ibn Tahir, is concluded in a manner far too perfunctory to be fully convincing. Another issue I have is with the sexual content, which, doubtless in accordance with 1930s era Yugoslavian censors, is downright aggravating in its non-specific suggestiveness, with endless descriptions of people “hugging” each other (the book would probably be quite a scorcher if all the lasciviousness it suggests were more concretely described).

But again, overall ALAMUT is an impressive achievement. The characterizations are appropriately complex, the multi-pronged narrative is inventive and dramatic, the historical detail feels authentic and there is, of course, a great deal of contemporary resonance. Perhaps most impressive of all is the presentation of Hasan-i Sabbah, a monstrous but very human figure who’s governed, like most everything else in this book, by emotions familiar to all of us. As quoted in the afterword by the translator Michael Biggins, Vladimir Bartol claims that his primary aims in writing ALAMUT were simply to answer the questions “is there anything that makes a person braver than friendship? Is there anything more touching than love? And is there anything more exalted than the truth?”