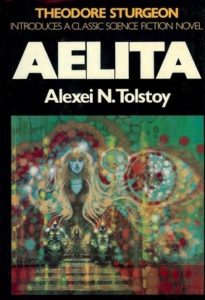

By ALEXEI N. TOLSTOY (Macmillan; 1923/81)

By ALEXEI N. TOLSTOY (Macmillan; 1923/81)

When reviewing a science fiction novel that’s nearly a hundred years old one obviously has to be forgiving. It’s a fact that science fiction dates faster and more dramatically than any other genre, especially when it hails from early-1920s Russia and involves the planet Mars, as is the case with AELITA by Alexei Tolstoy (1882-1945).

Tolstoy was something of a pioneer in Russian science fiction, with AELITA, his best-known work, appearing in 1923. It was made into a famous silent film (1924’s AELITA: QUEEN OF MARS) and remains in print today. That doesn’t mean, however, that it’s an especially good book; note how Theodore Sturgeon, in his introduction to the 1981 translation under review, desperately ties himself into knots trying to find something worthwhile—he seems inordinately impressed that Tolstoy foresaw the invention of television—about what is a frankly ridiculous story.

It begins with Alexei Gusev, a soldier, finding a note stuck to a wall inviting anyone wanting to travel to Mars to turn up at the home of Los, a widowed engineer who’s built a spaceship for that very purpose. After meeting with Los and saying goodbye to his long-suffering wife Masha, who gets a chapter devoted to her before disappearing from the narrative (and never learning where her hubbie is going), Gusev joins Los.

The trip to the red planet is unbelievably smooth and speedy (although the book has been praised for depicting interstellar flight with at least some accuracy), and the surface of Mars remarkably Earth-like but for some odd creatures. Before long Los and Gusev happen upon a Martian, who resembles a “man of medium height” who flies around in a gyrocopter-like contraption.

Los and Gusev meet several more Martians, among them the title character, a psychically-endowed beauty with whom Los falls in love. It seems Aelita and her fellow Martians hail from Earth—Atlantis, specifically, which they escaped via space ships that deposited them on Mars, a virgin landscape the Atlanteans wasted no time colonizing. This is related via a couple of lengthy monologues set in the middle of the book that have the effect of slowing things down appreciably.

Thankfully the novel is quite short overall, and picks back up with the exploits of Gusev, who is determined to make Mars part of the Soviet Union. In the process he becomes embroiled in a political coup against the Martians’ ruling leader, in an atmosphere of anarchy and unrest mirroring that of Russia at the time of this novel’s writing. It all concludes with an action-intensive series of fights, captures and escapes, and an ending that would appear to leave things open for a sequel—for which I for one am not holding my breath!