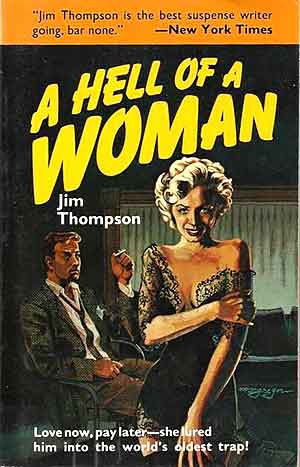

By JIM THOMPSON (Black Lizard; 1954/84)

One of five novels published by the late Jim Thompson in 1954, A HELL OF A WOMAN hails from the most fertile period of his career. That explains why it’s so typical of his work in so many respects: the terse hard-boiled prose, doom-laden trajectory, overtly misogynistic treatment of the fairer sex (women in this novel are knocked around regularly) and copious 1950s-era profanity (“The job stinks. The town stinks. You stink. And there’s not a goddamned thing you can do about it”) are all Thompson trademarks. Yet A HELL OF A WOMAN also has an overtly experimental angle that sets it apart from Thompson’s other books (and also its 1979 French language film adaptation SERIE NOIRE).

Frank “Dolly” Dillon, who narrates the book, is (like most Thompson headliners) a loser. While working as a door-to-door salesman and bill collector for the corrupt Pay-E-Zee Store chain, Dolly meets Mona Farrell, a young woman who “was about as far from being a raving beauty as I was,” but who enchants him nonetheless. Dolly’s protective instincts are aroused when he learns that Mona is being essentially held prisoner by her ultra-bitchy aunt, who forces her niece to prostitute herself for money.

Dolly for his part lives in “a little four room dump on the edge of the business district” with his much-hated wife Joyce. Their relationship is rife with abuse and resentment, and when Dolly inevitably lands himself in jail Joyce isn’t the one to bail him out; rather, it’s Mona who does so, with money filched from her aunt. Apparently, the old bag is quite loaded, sitting on a $100,000 stash (equivalent to over a million in today’s currency), leading Dolly to concoct a decidedly amoral scheme that—spoiler alert!—involves theft and murder.

So far, so Jim Thompson. But around the halfway point Dolly goes schitz and comes to view his situation from two separate vantage points, conveyed via alternating chapters. In one of them he describes his situation in an optimistic (though still cynical and profane) light, shamelessly whitewashing his already-described actions, while in the other Dolly recounts the cold hard reality he faces. The two viewpoints converge in the final chapter, whose last paragraph consists of dual sentences, one italicized and one not (the publisher’s decision, apparently, as Thompson wanted the sentences separated into columns). Neither ends happily.