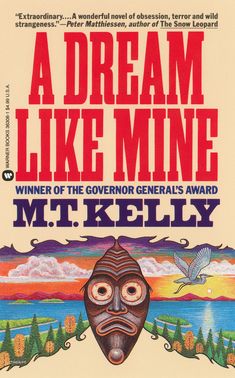

By M.T. KELLY (Warner Books; 1987/1992)

By M.T. KELLY (Warner Books; 1987/1992)

The issue of Native American exploitation is given an alternately gritty and hallucinatory airing in A DREAM LIKE MINE, a starkly violent thriller with a mystical edge. The setting is an Indian reservation in Ontario, Canada, where an unnamed white male reporter is thrust into an intense drama involving an outraged Native American (or, as they’re known in Canada, First Nations) man.

The reporter protagonist, who narrates, is at the reservation to write an article about native healers. He begins his odyssey by attending a sweat ceremony, which entails an immersion in a dark lodge filled with heated rocks, meant to induce visions. In doing so the reporter is introduced to Wilf, an ancient shaman, and a protégé of Wilf’s named Arthur, who from the start seems quite hostile. That hostility only increases as the reporter’s stay in the region stretches on, and eventually explodes in an orgy of violence.

Arthur’s rage entails the kidnapping of Bud, the CEO of a chemical company responsible for polluting the reservation’s waters. The reporter is taken hostage for what quickly turns into a grueling odyssey of torture and indiscriminate killing, during which the reporter comes to share the mystical visions experienced by Wilf and Arthur. He’s also forced to account for the atrocities committed by his ancestors, to which end the author includes a number of unpleasant historically-based tidbits (such as an Indian woman’s infant snatched from her breast and thrown to dogs by white soldiers).

The reporter’s first person recollections can admittedly be stifling at times; he’s given to introspective ruminations that often blunt the effect of an otherwise admirably unsparing account. But then again, it’s a testament to how thoroughly the author has fleshed out the character that his personality quirks register so strongly.

Wilf and Arthur are likewise extremely well delineated, three-dimensional characters, whose foibles belay the standard saintly and stoic media depiction of Native Americans. The result is a fully rounded account that brings up many troubling questions about exploitation and outrage, questions that certainly aren’t confined to fiction, and whose answers are anything but simple.